EC Comics

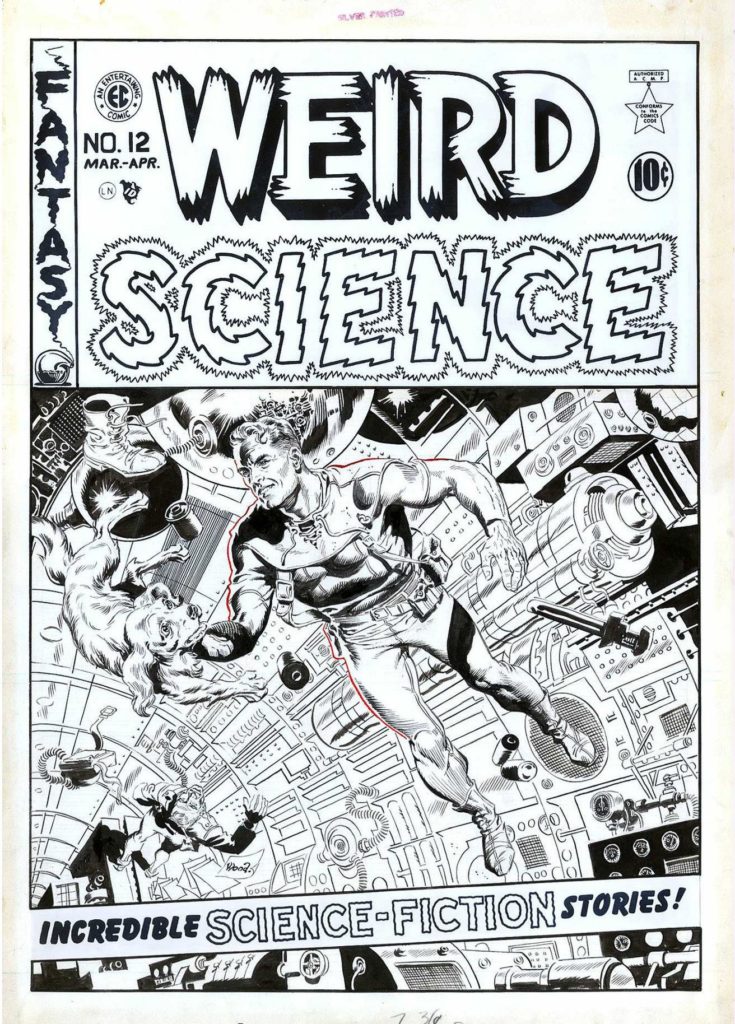

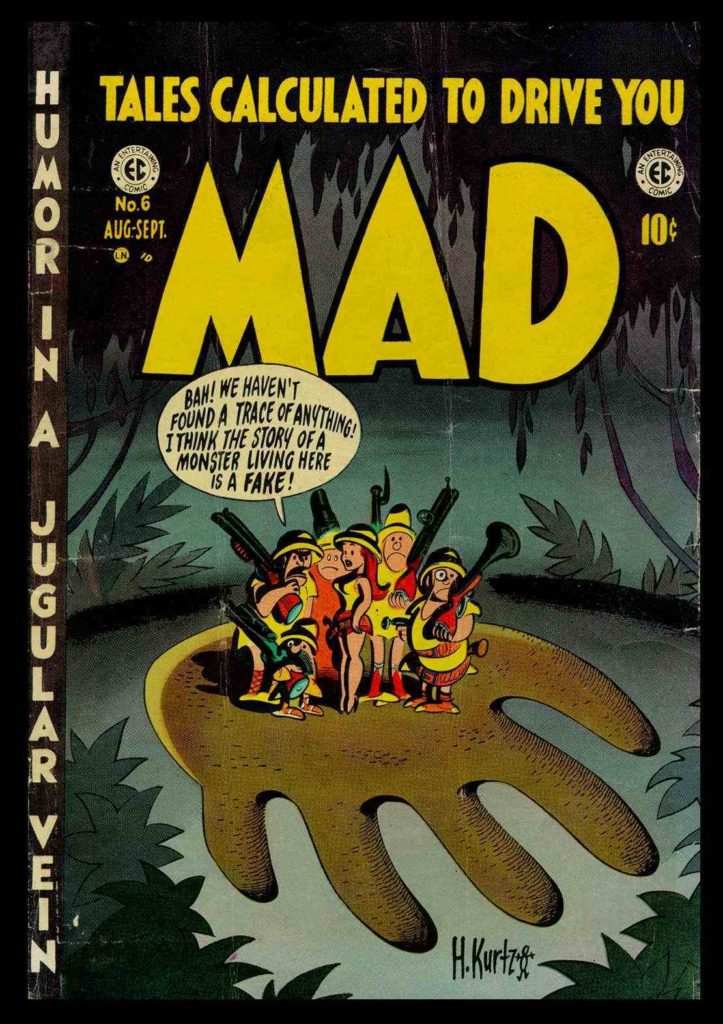

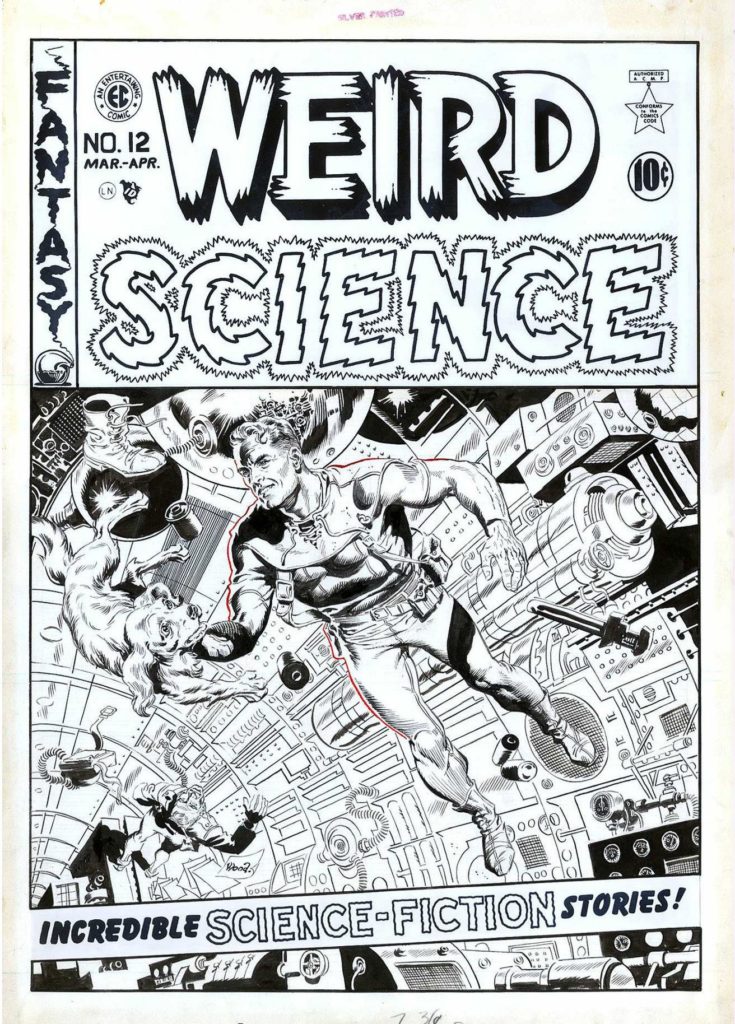

EC comics (First “Educational Comics” then later “Entertaining Comics”) was the biggest publisher of comics between 1950-1955. They published comics in genres like horror, war, romance, fantasy, funny animal, and satire. Max Gaines, who was a co-publisher of All Star Comics in the 40s, founded EC comics in 1944 when that company merged with DC comics. After his death in 1947, his son, Bill Gaines took over. Bill transformed the company into a pioneer of horror, science fiction, and satire comics. While you may not have heard of “EC Comics”, you probably have heard of “Tales from the Crypt“, “Weird Science“, and “Mad Magazine“, for example.

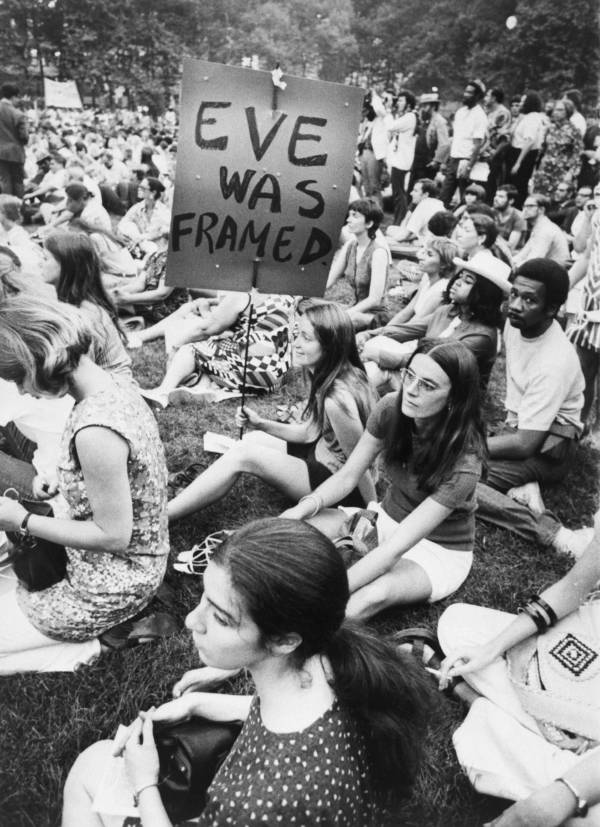

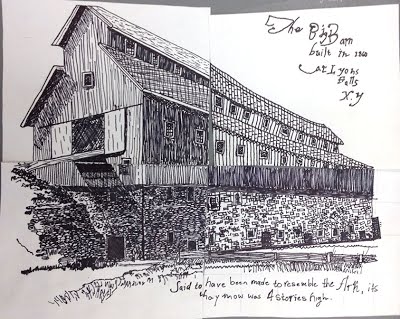

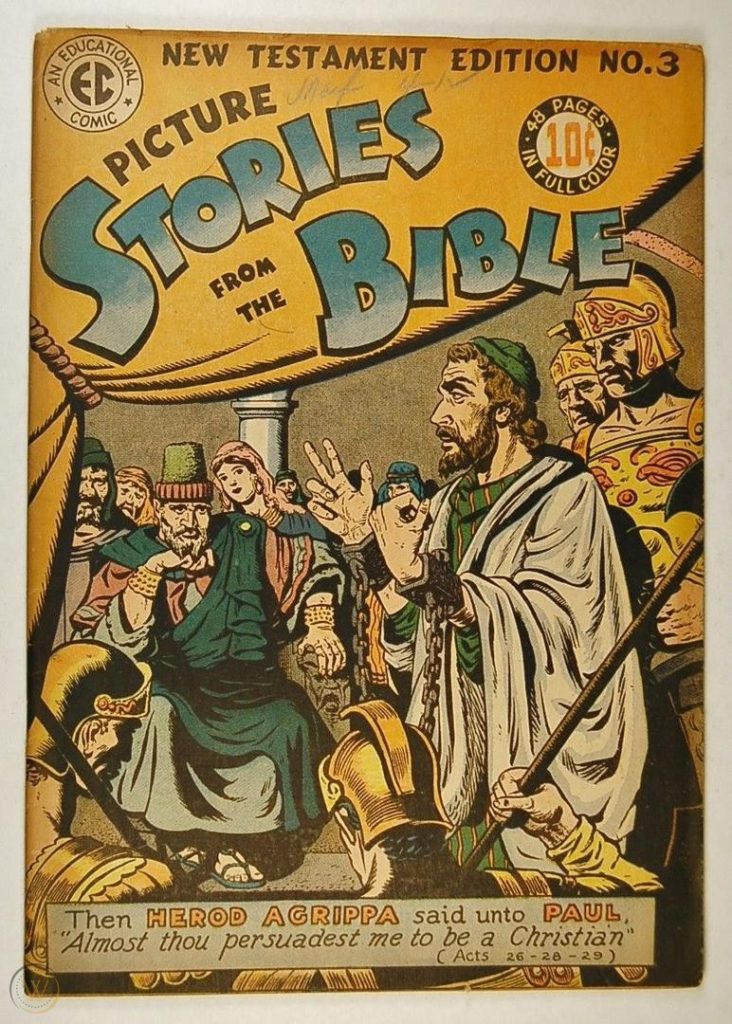

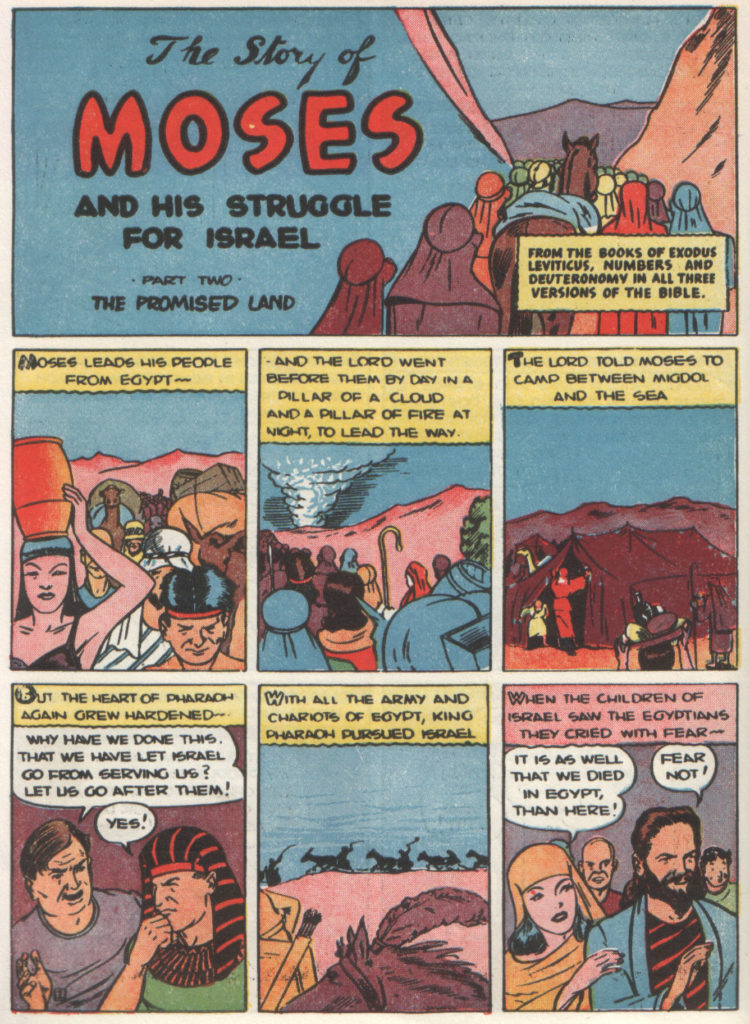

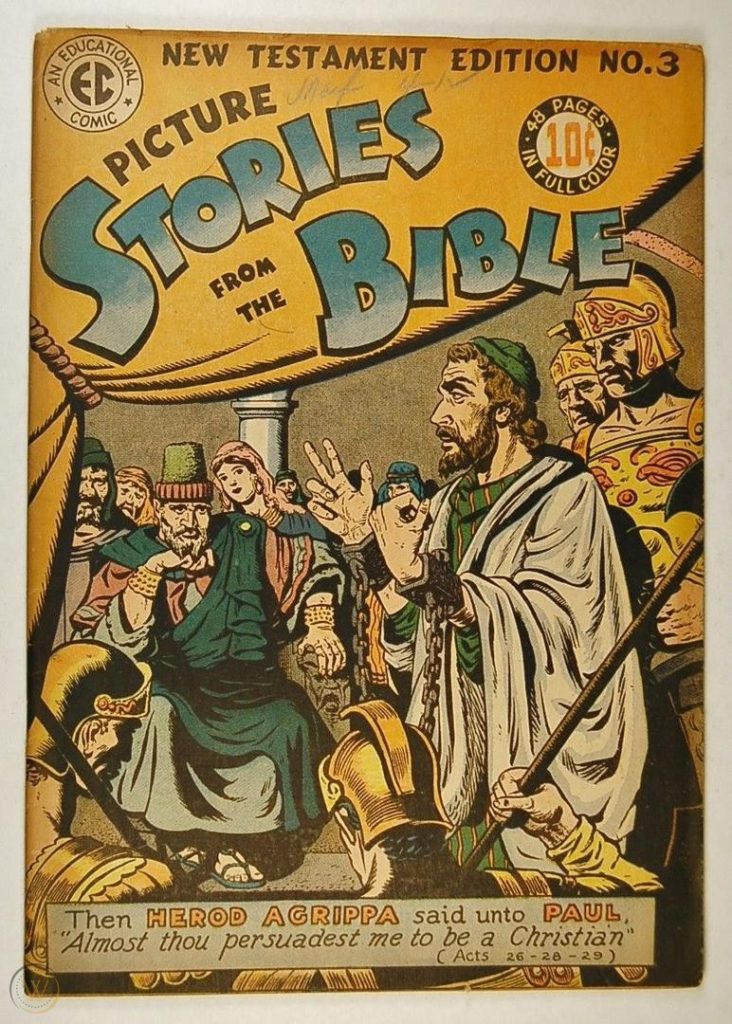

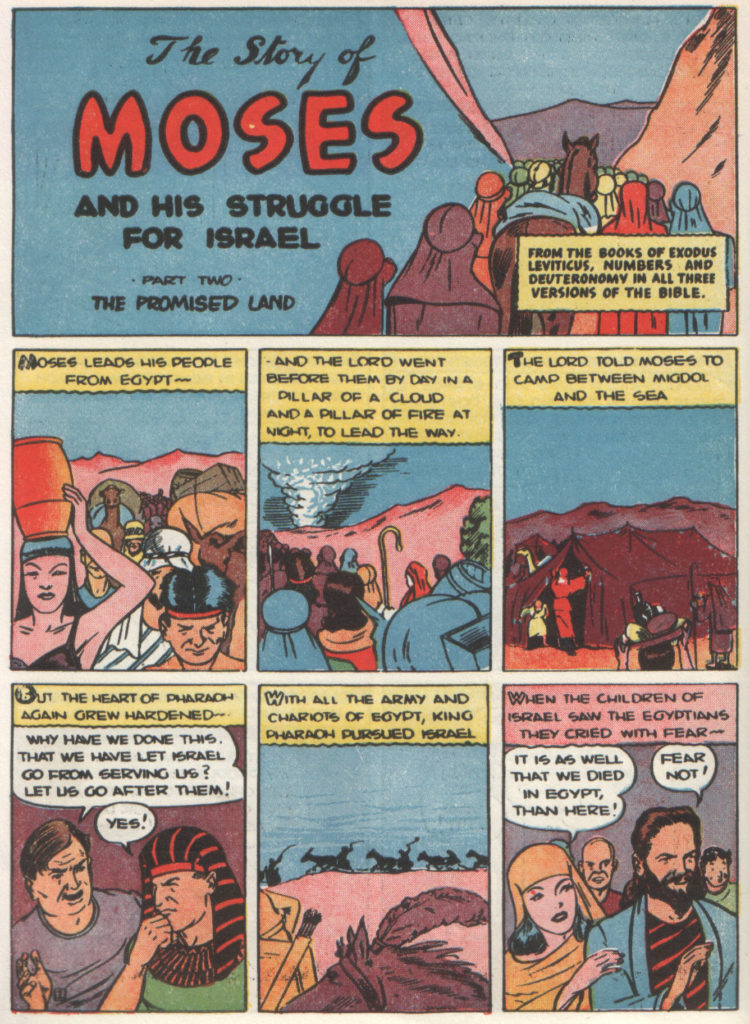

When Max started the company he began by producing a line of Picture Stories from the Bible.

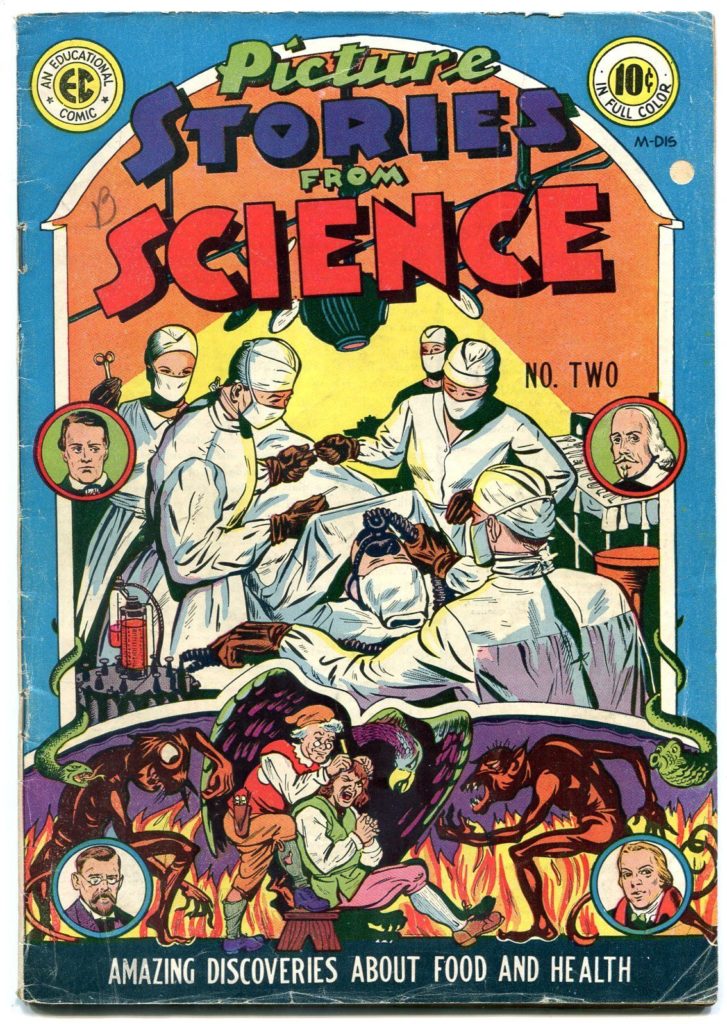

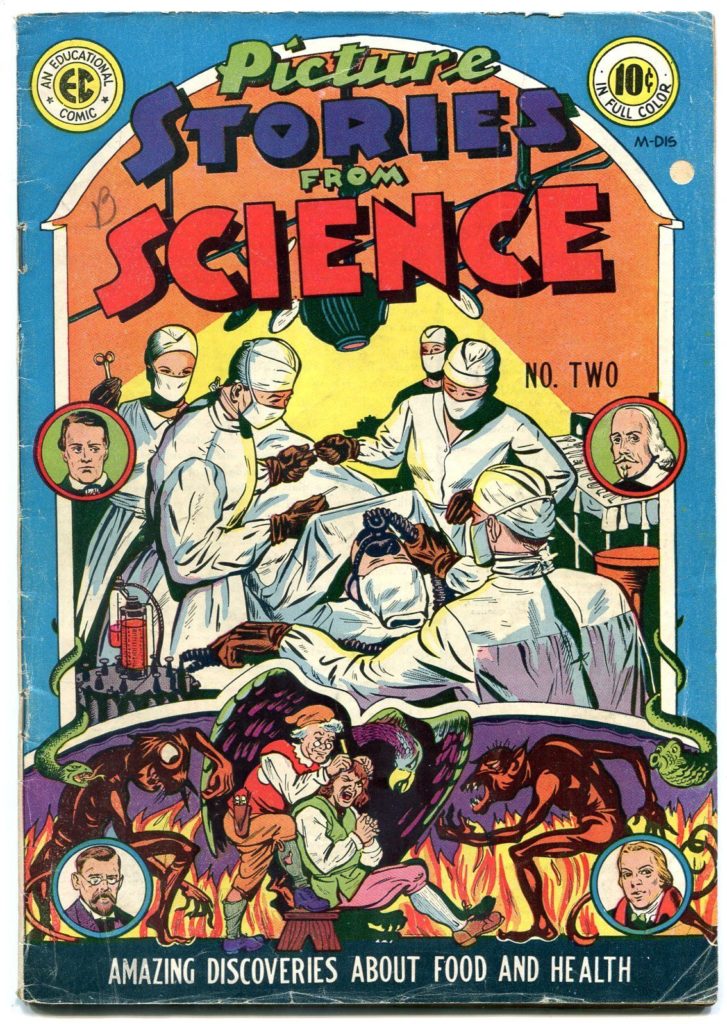

He also published Picture Stories from Science

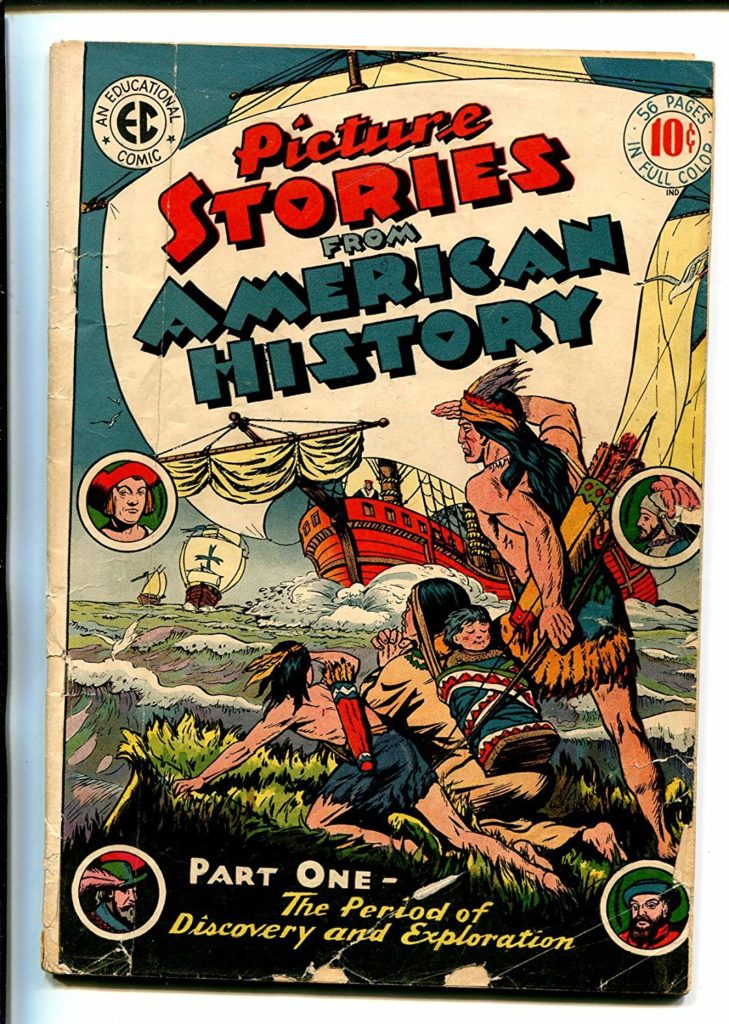

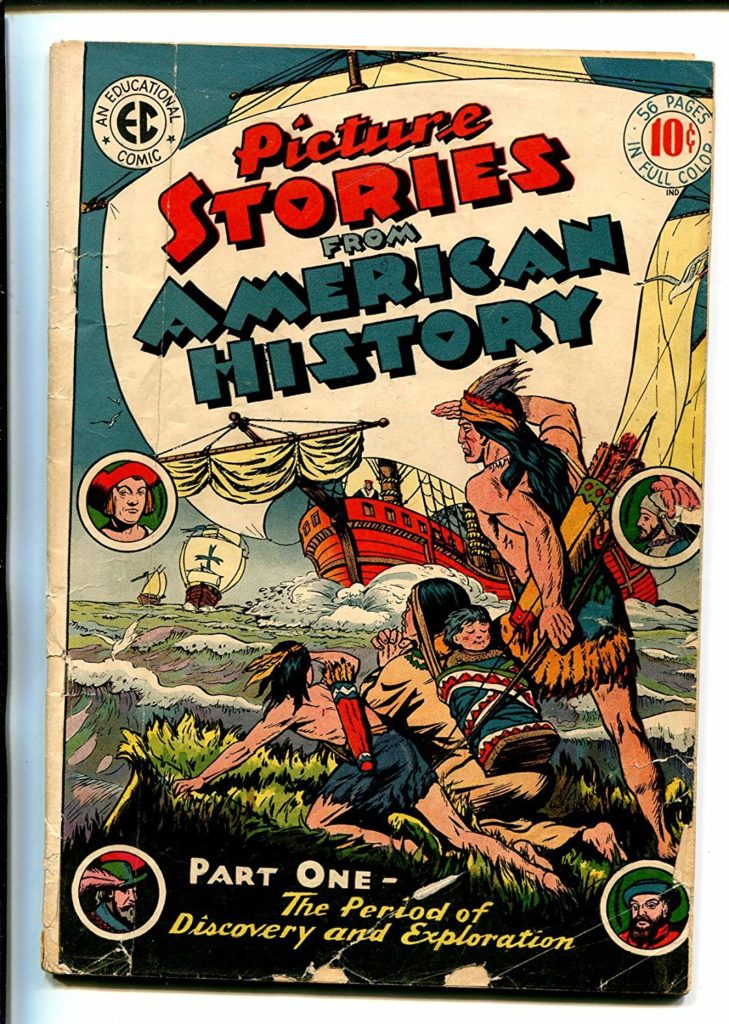

…and Picture Stories from American History/

Which are all exactly what you think they are.

The company was approximately $100,000 in debt when he died in a boating accident.

His son, Bill Gaines, a chemistry student and aspiring teacher, was left in charge of the company.

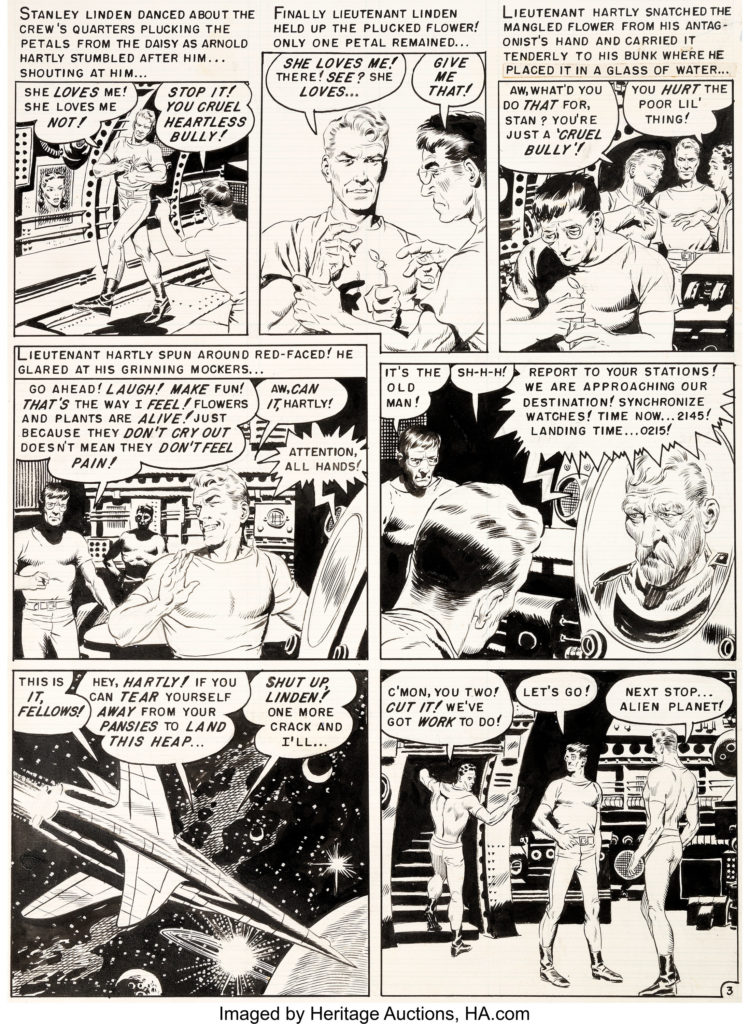

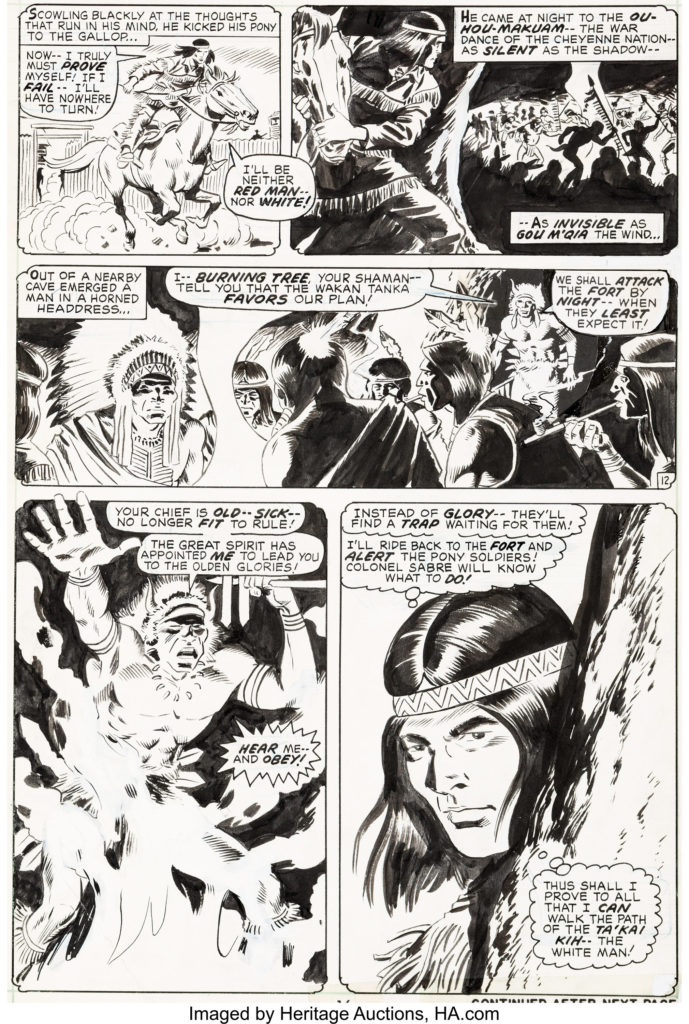

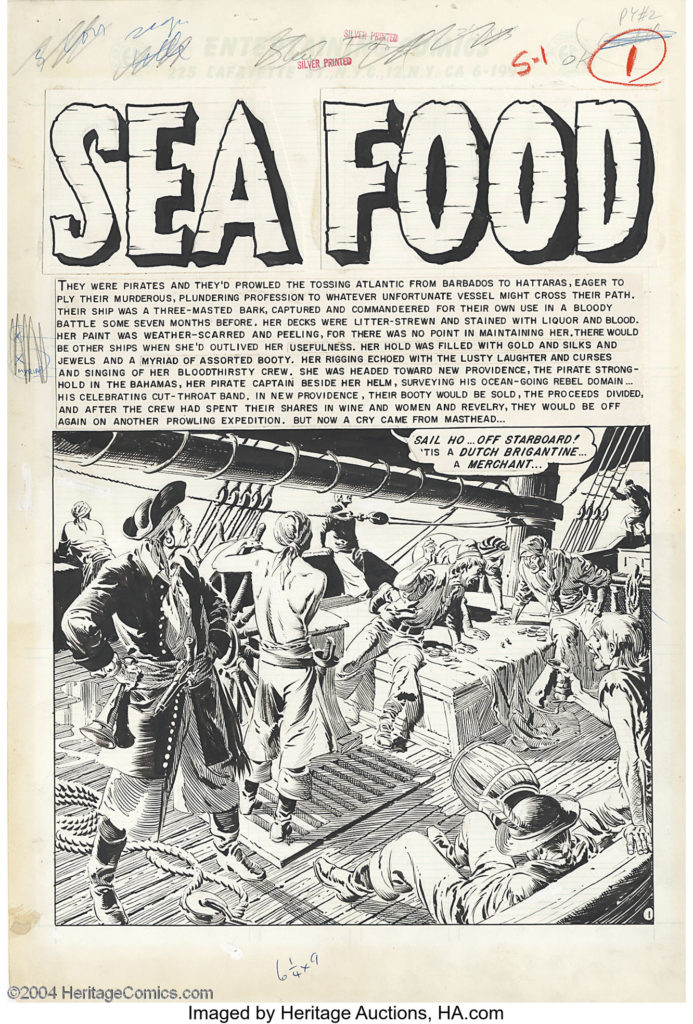

Bill changed the name from Educational Comics to Entertaining Comics and decided to try and capitalize of the popular genres of the day. His first publications were character driven like the comics that preceded EC in the 40s.

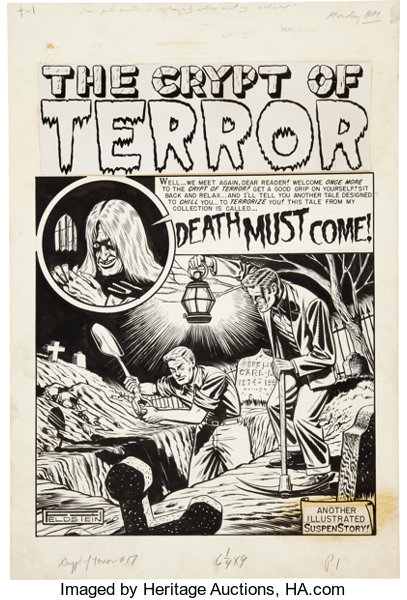

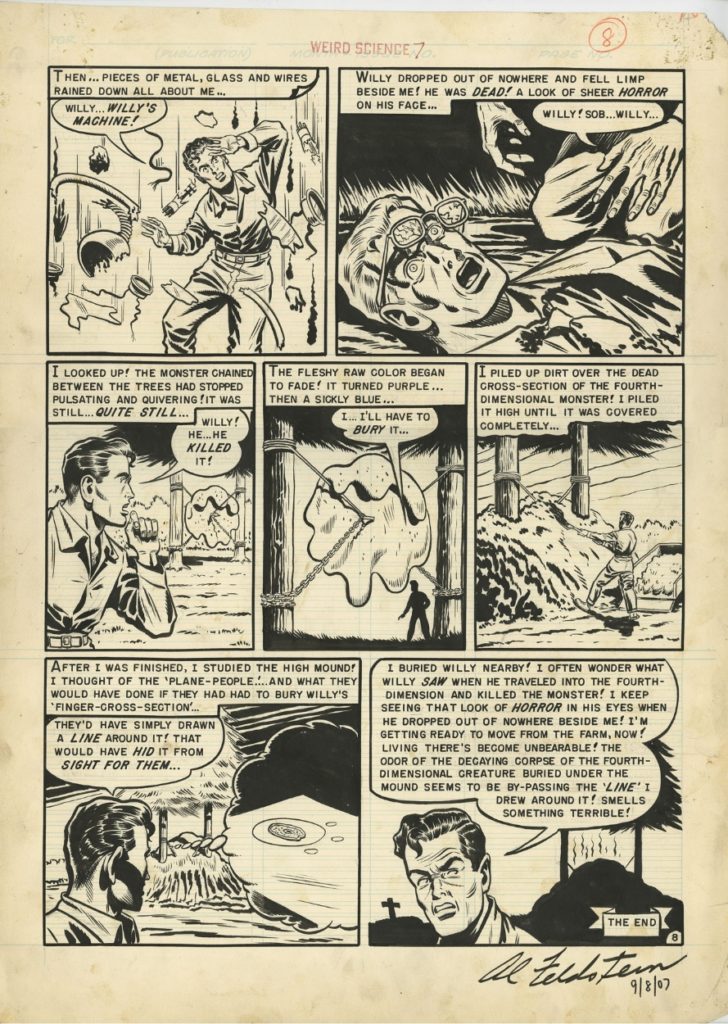

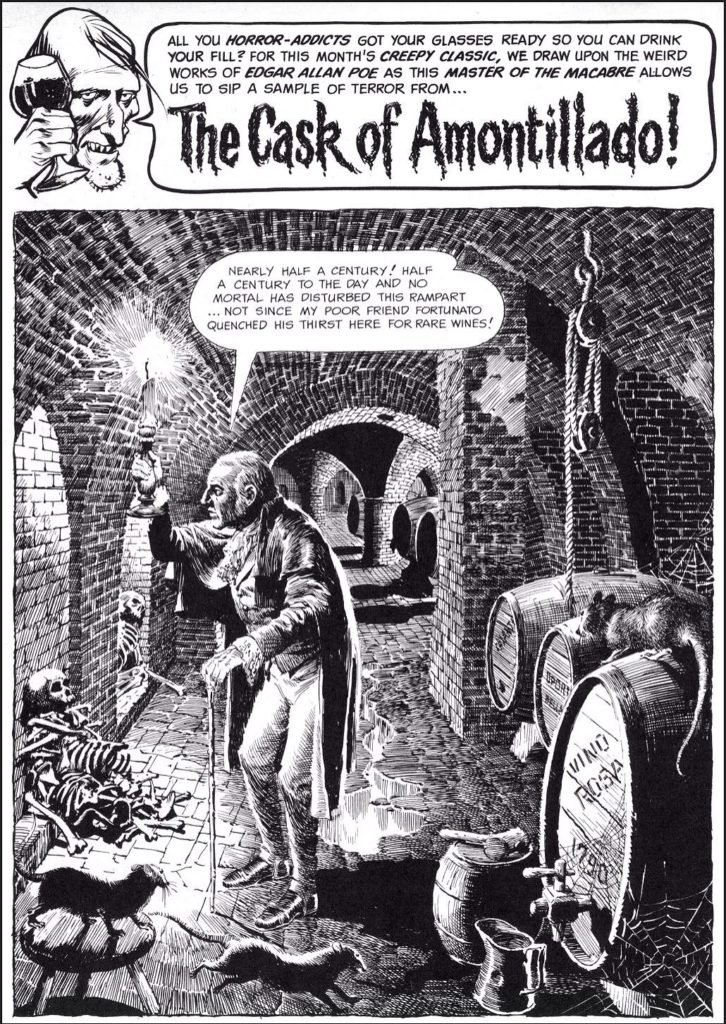

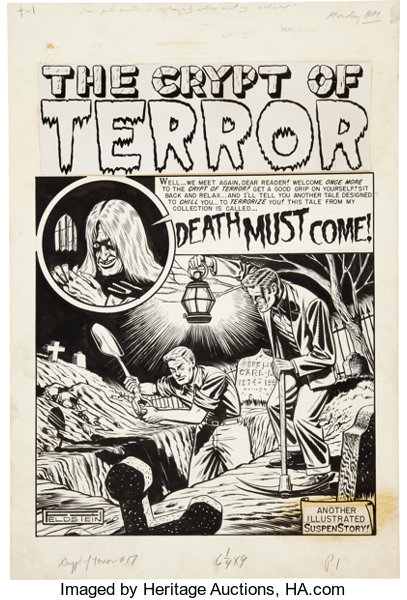

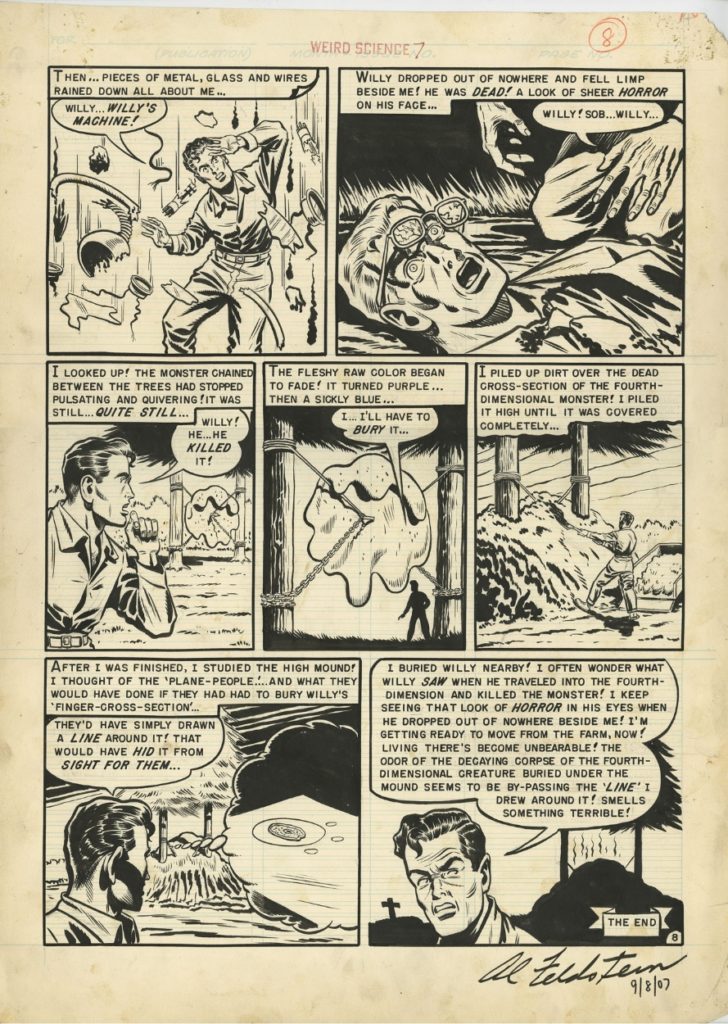

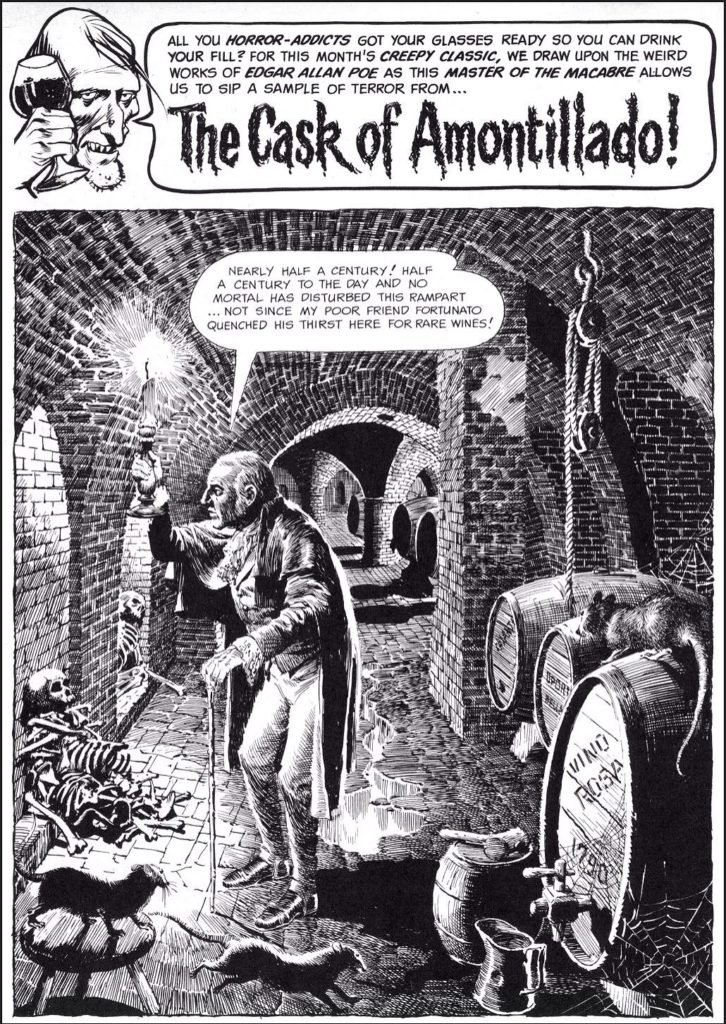

In 1950, Al Feldstein became the editor of the company. He and Gaines decided to take the books in a completely new direction.

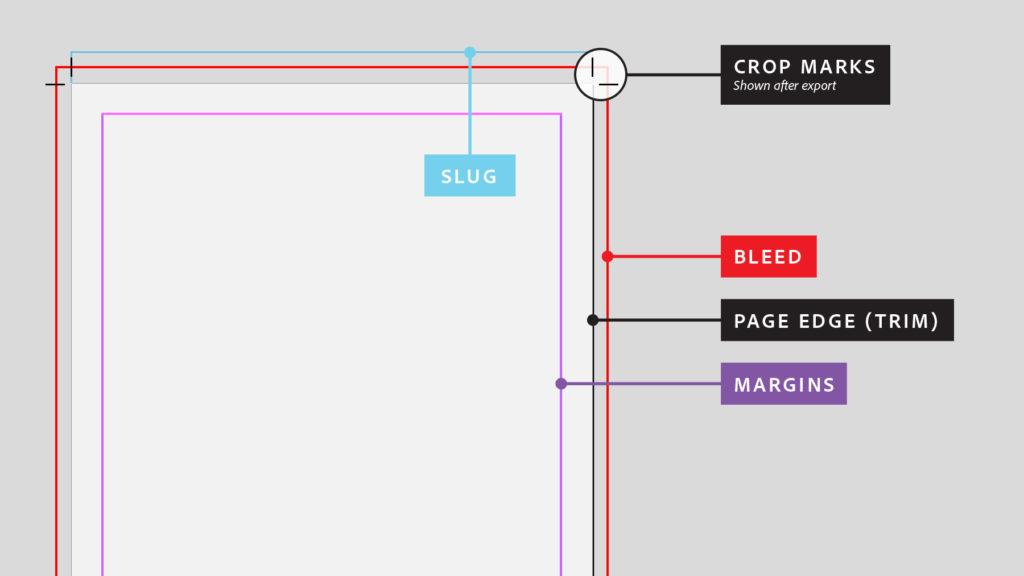

Most of their books were anthology comics, meaning, they did not feature a main character, but rather, sought to tell a variety of stories in the genre specified by each magazine’s genre. These stories would often be 4-8 pages long. The reason many comics are presented in 4 page units (you will often hear about 4 page, 8 page, 12, page, 16 page, 20 page, 24 page, etc comics is because when comic magazines are printed they are printed in 4 page signatures.

We will begin by discussing their main contributors:

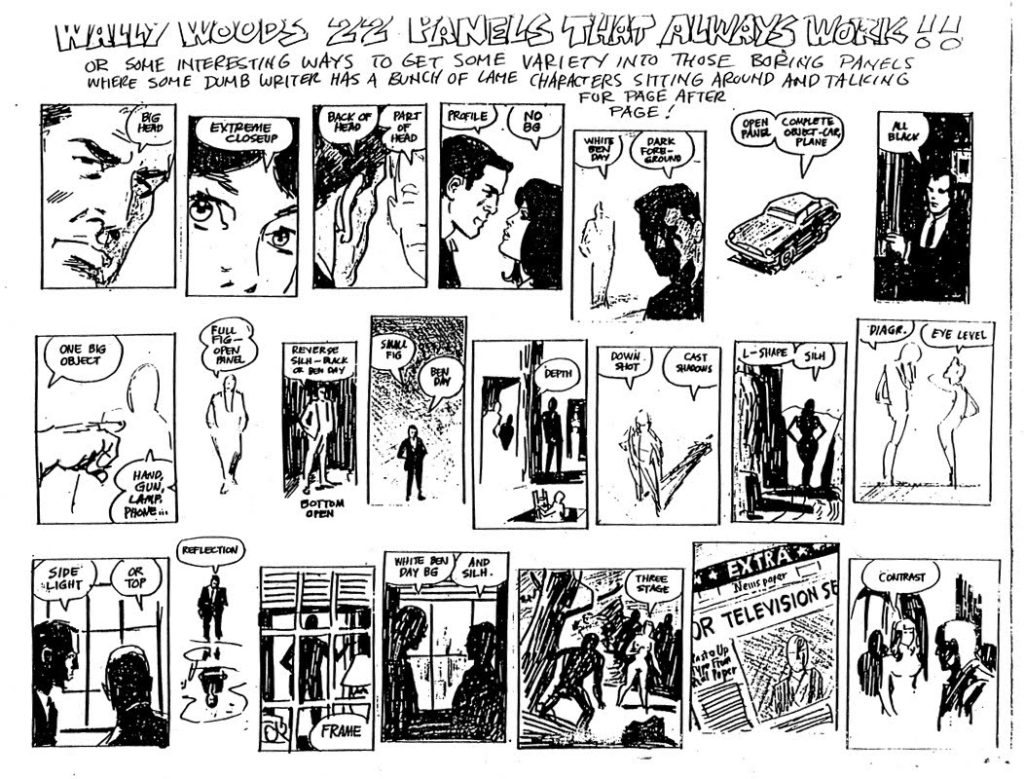

Al was an illustrator, but began writing comics at EC. He eventually stopped drawing interiors to focus on writing and cover art. He would often write a 4-8 page story for 7 magazines in the EC line every month.

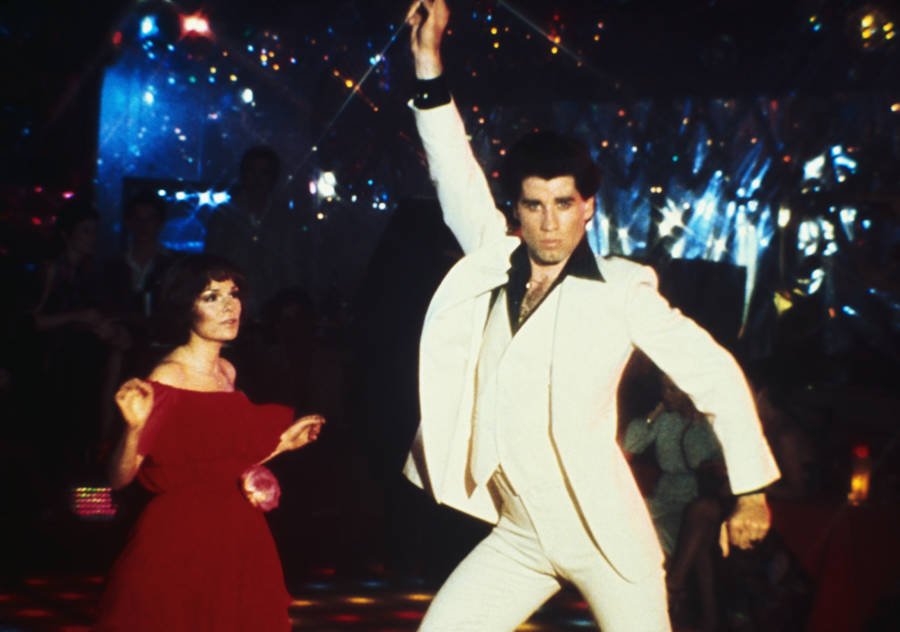

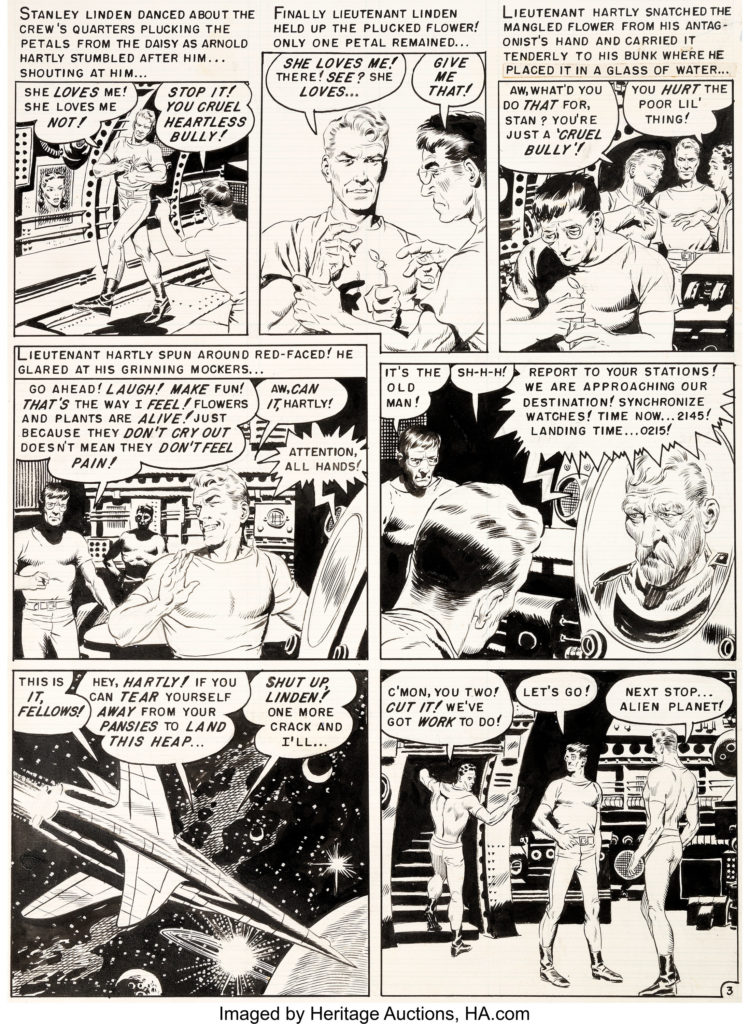

was the super star artist of the EC line. He became primarily known for his Sci-Fi comics, but the real secret behind the success for the EC line was the fact that he and Feldstein weren’t scared to get a little smutty with their depictions of romantic relationships.

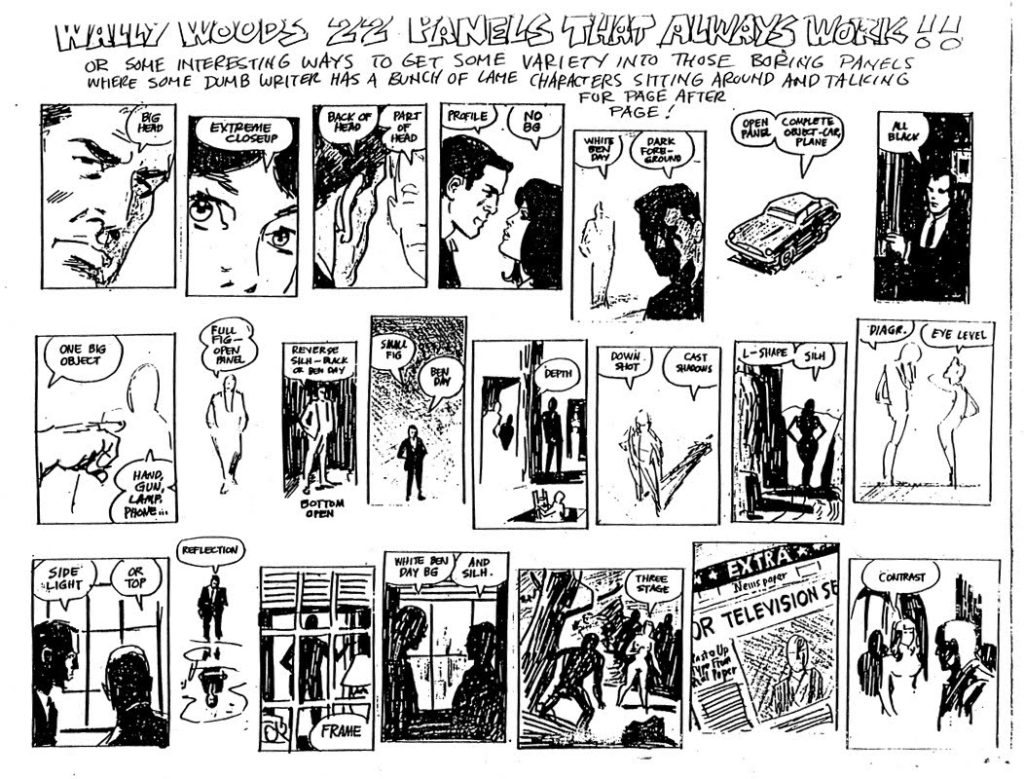

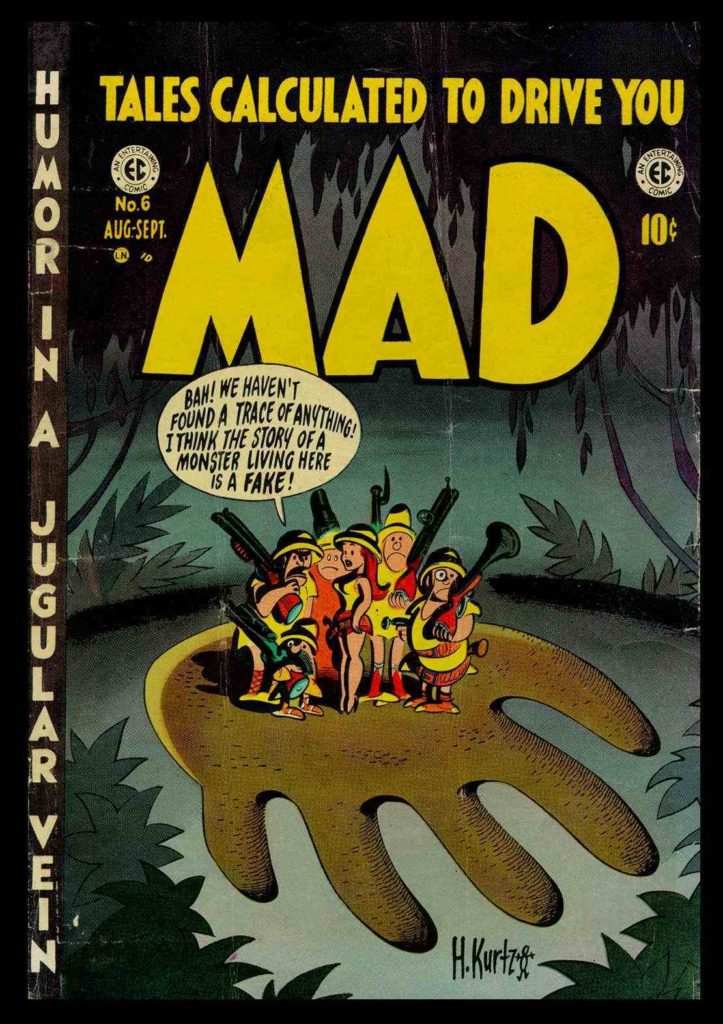

He wrote and edited theTwo-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat war comic books, where he also drew many of the carefully researched stories, before he created his most-remembered comic book, Mad, in 1952 which was a humor and satire book.

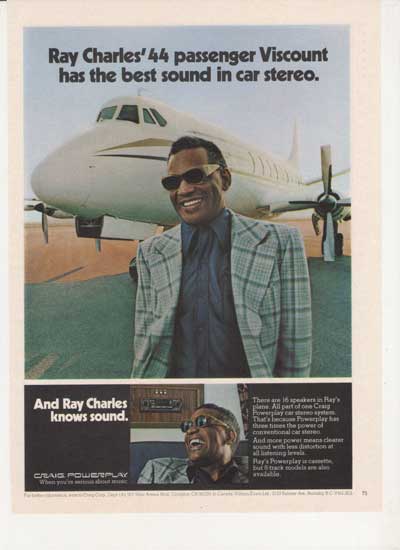

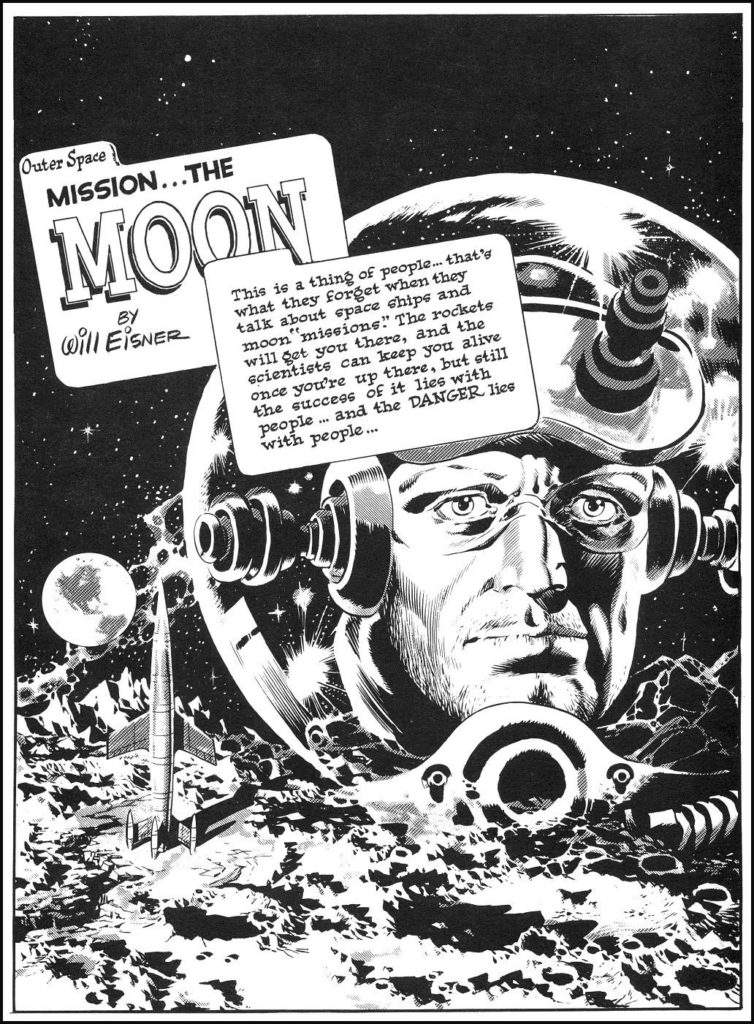

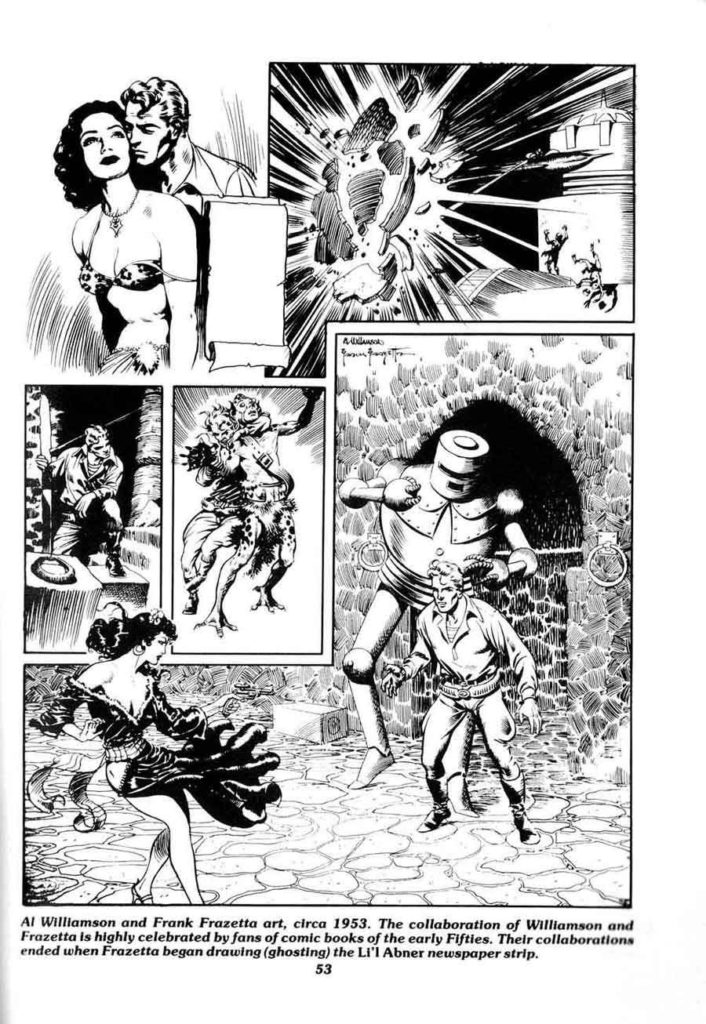

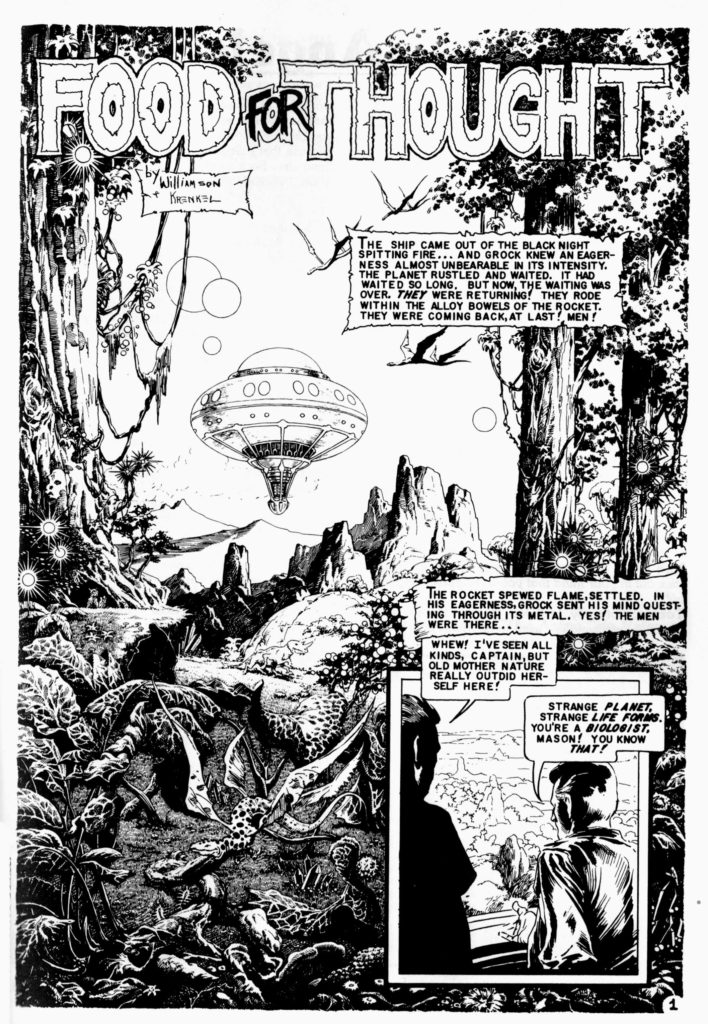

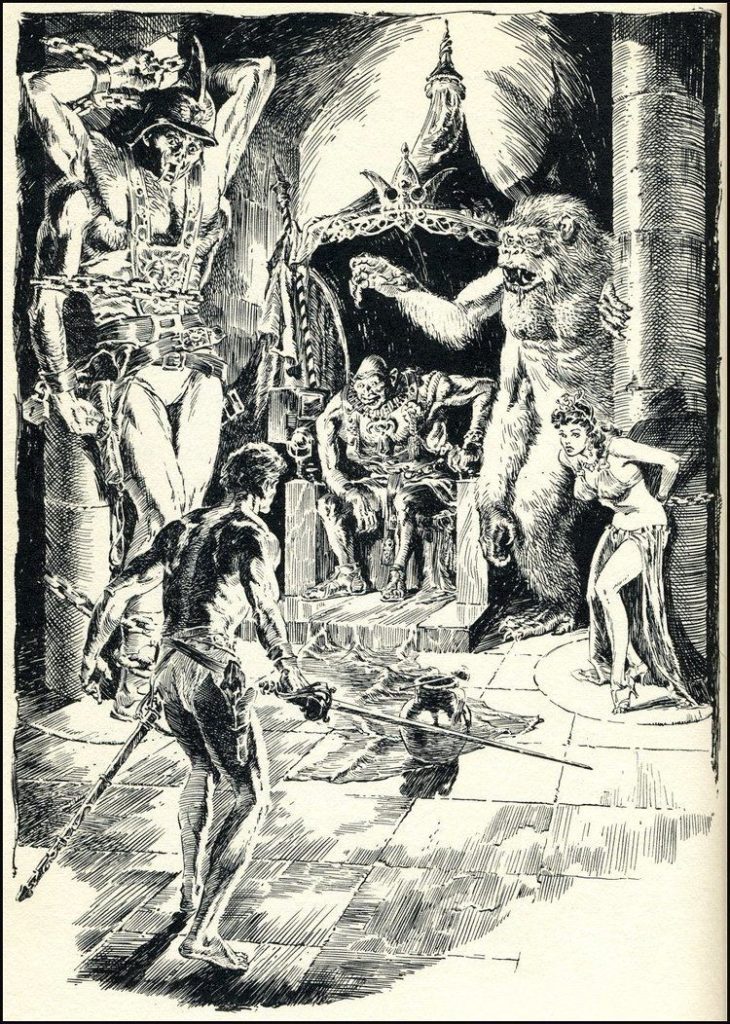

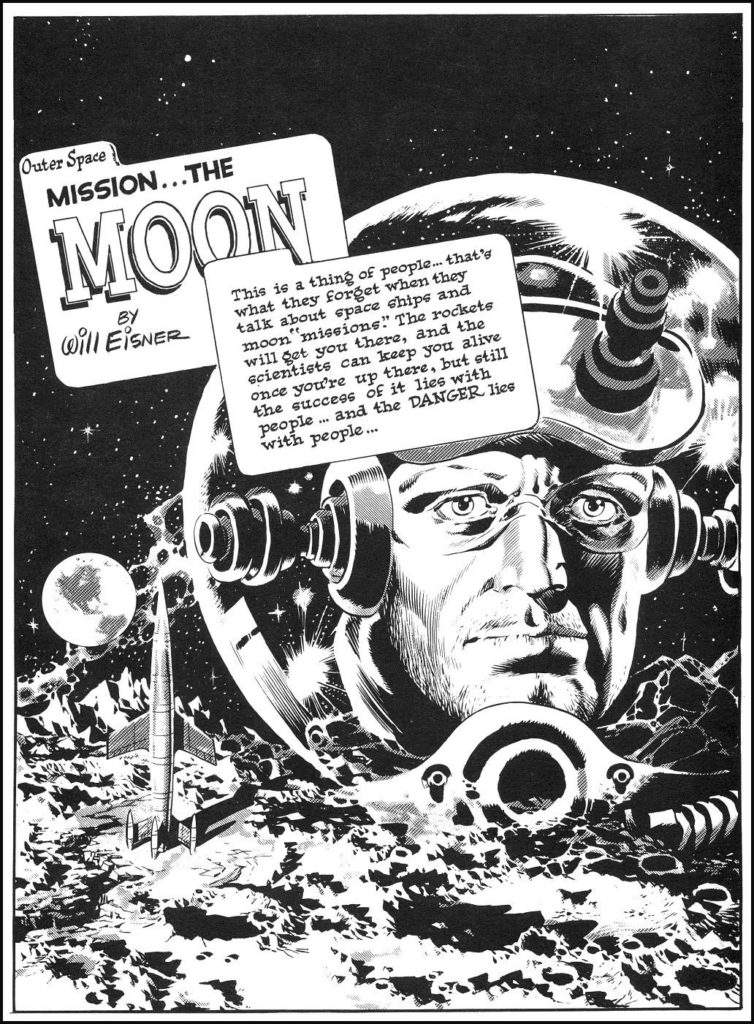

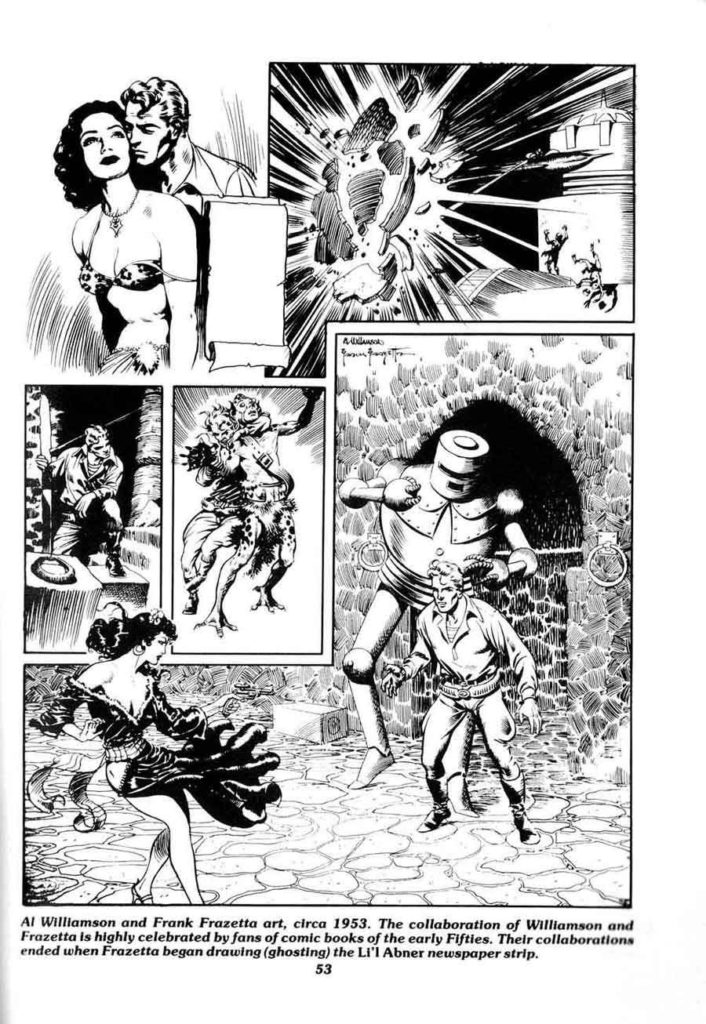

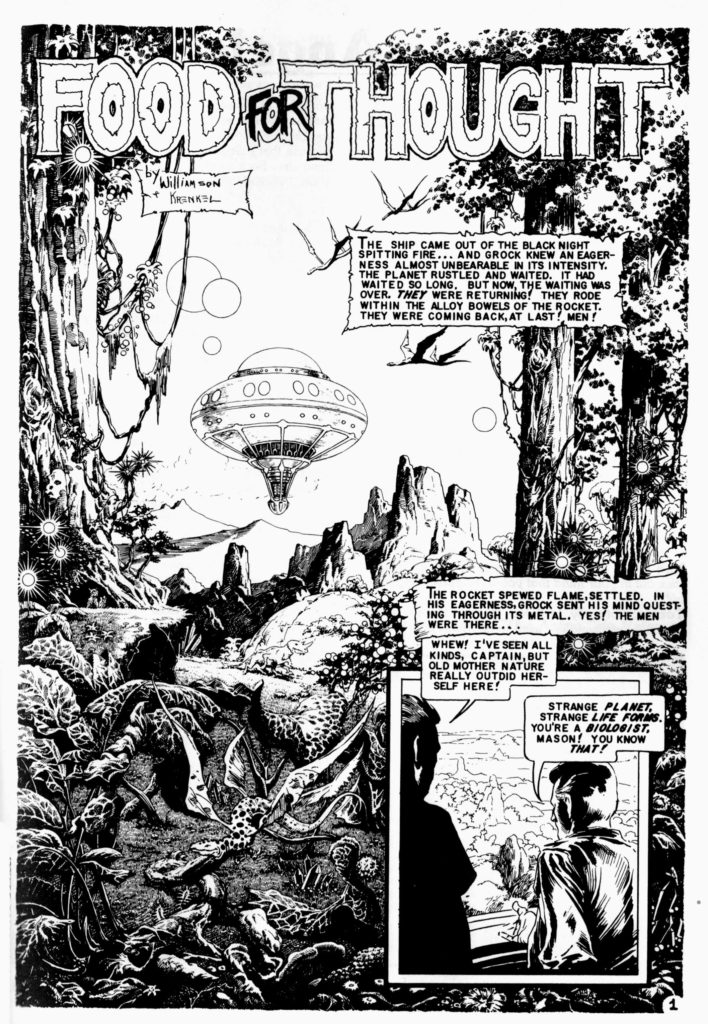

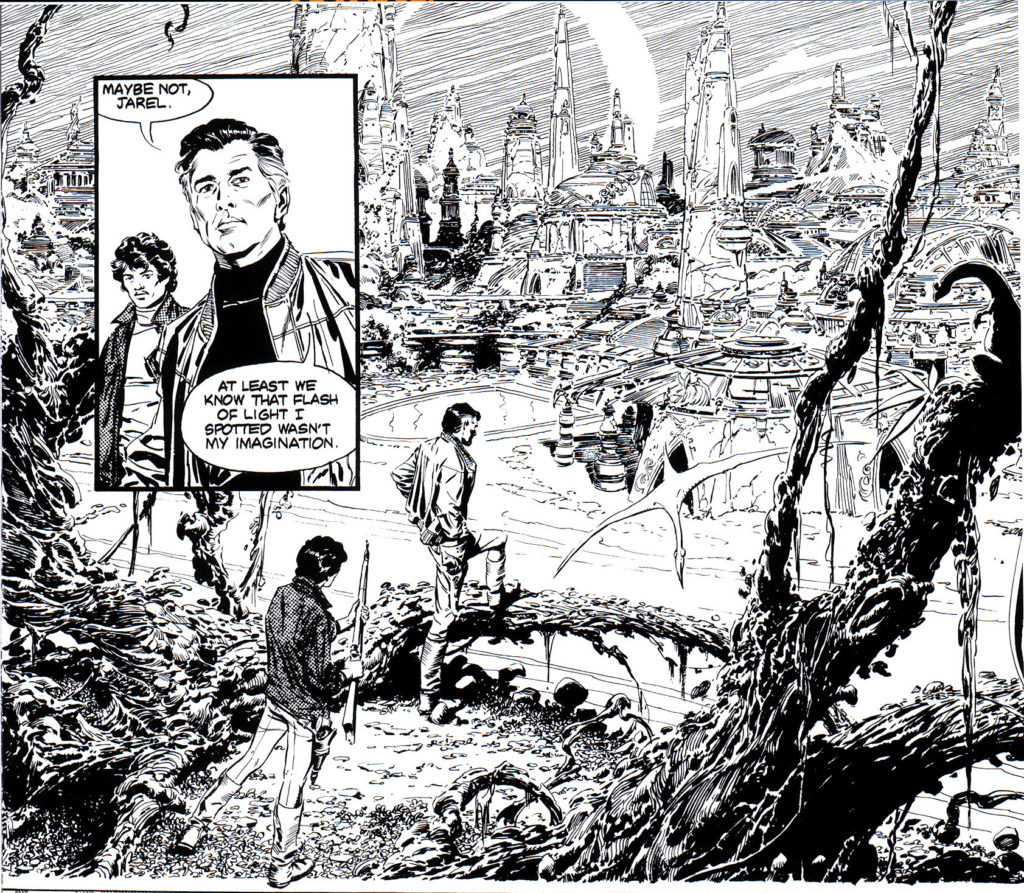

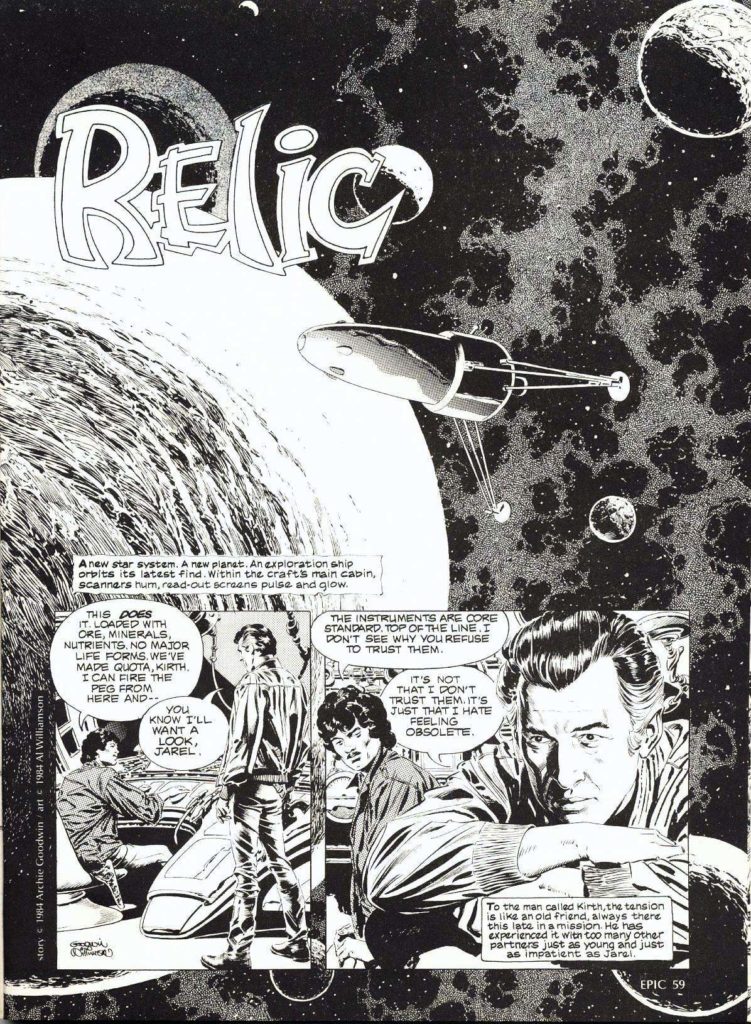

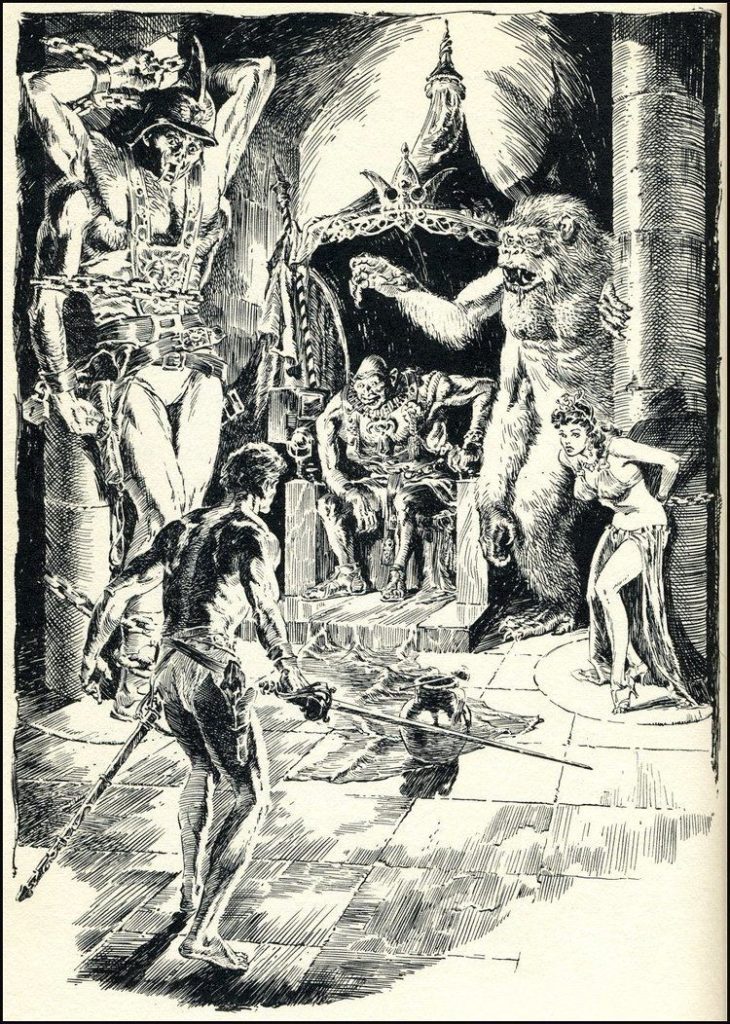

He took art classes at Burne Hogarth‘s Cartoonists and Illustrators School, there befriending future cartoonists Wally Wood and Roy Krenkel, who introduced him to the work of illustrators who had influenced adventure strips. Before long, he was working professionally in the comics industry. His most notable works include his science-fiction/heroic-fantasy art for EC Comics in the 1950s, on titles including Weird Science and Weird Fantasy.

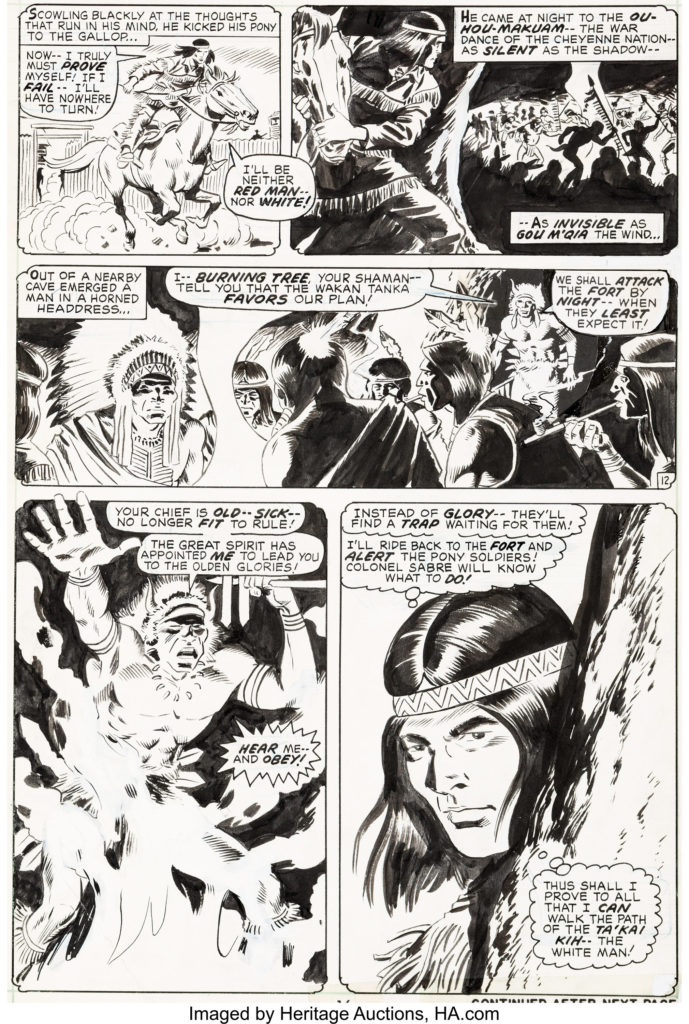

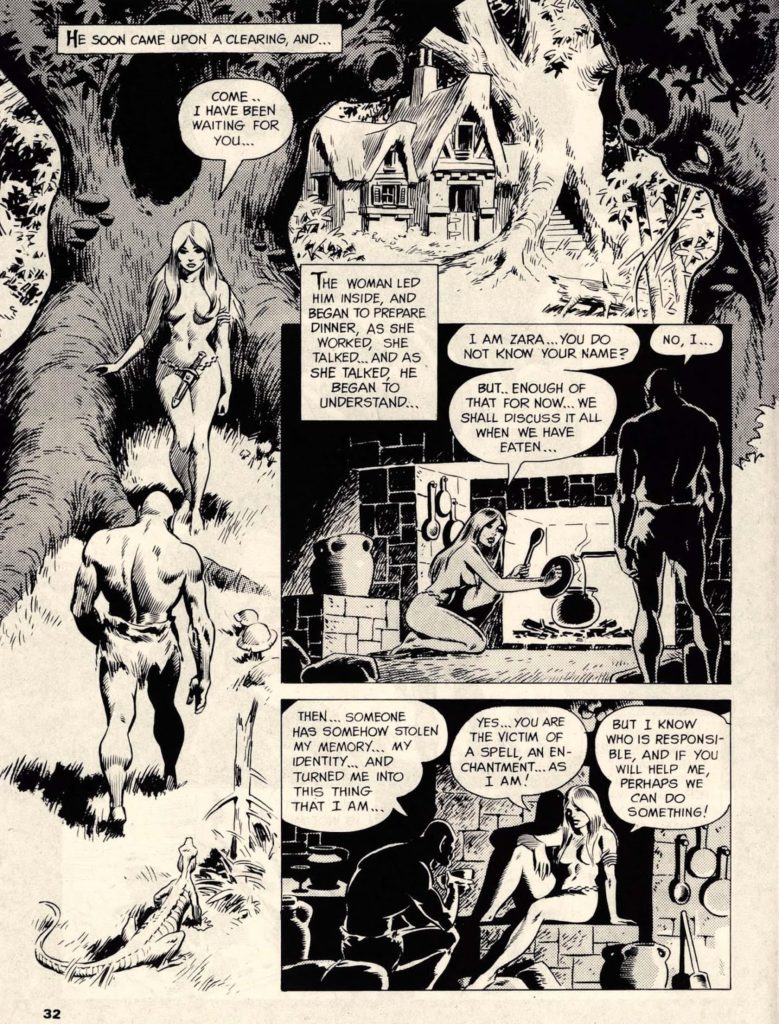

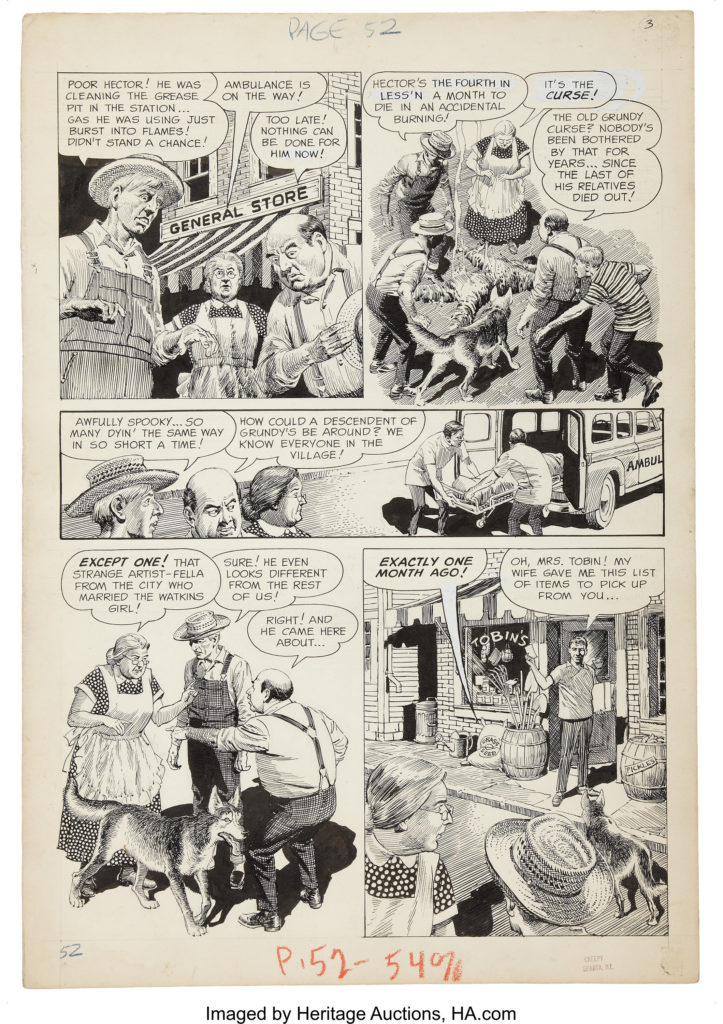

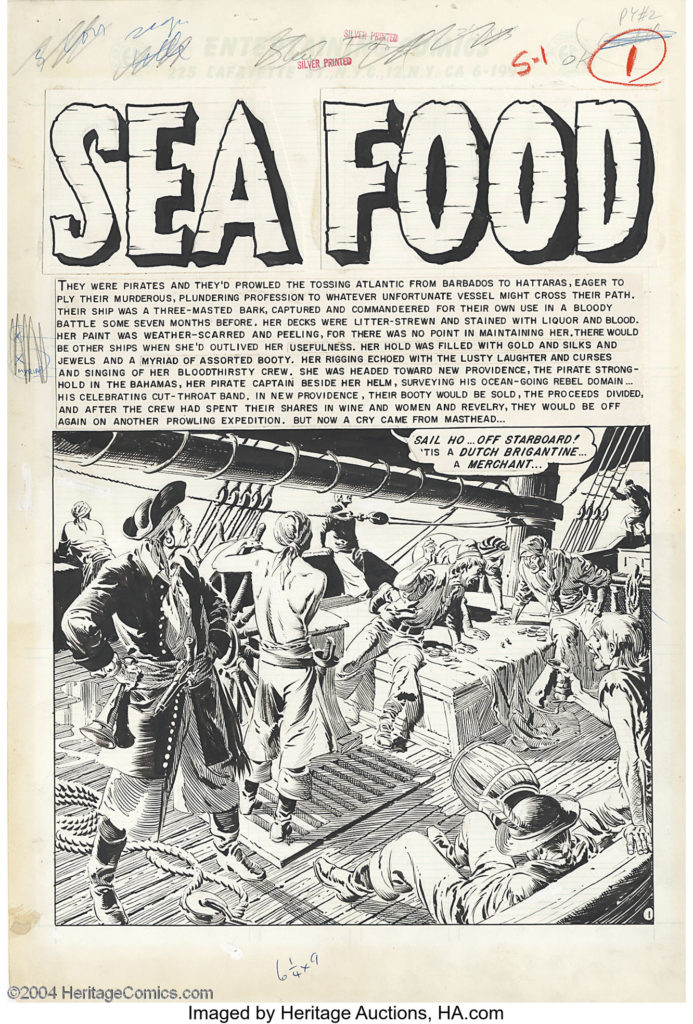

Crandall drew for comic books from 1939 until 1973. His first work appears in comics from publisher Quality Comics, for which he drew stories starring such superheroes as the Ray (in Smash Comics, beginning in 1941 and initially under the playful pseudonym E. Lectron)[12] and Doll Man (first in Feature Comics in 1941, then in the character’s own solo title). His earliest confirmed cover art is for Fiction House‘s Fight Comics #12 (April 1941) at the Grand Comics Database.[13] Other early work includes inking the pencil art of future industry legend Jack Kirby on two of the earliest Captain America stories, “The Ageless Orientals That Wouldn’t Die”, in Captain America Comics #2 (April 1941),[14] and “The Queer Case of the Murdering Butterfly and the Ancient Mummies” in #3 (May 1941).[15]

With S.M. “Jerry” Iger credited as writer, Crandall co-created the superhero the Firebrand in Quality’s Police Comics #1 (Aug. 1941) and began his long run as artist of his signature series, the World War II aviator-team strip “Blackhawk“, in Military Comics #12-22 (Oct. 1942 – Sept. 1943) and, after his WWII service in the Army Air Force,[8] in Blackhawk and in Modern Comics. During this time he also drew the adventures of Captain Triumph in Quality’s Crack Comics. His final “Blackhawk” work was a seven-page story, plus the cover, for Blackhawk #67 (Aug. 1953).

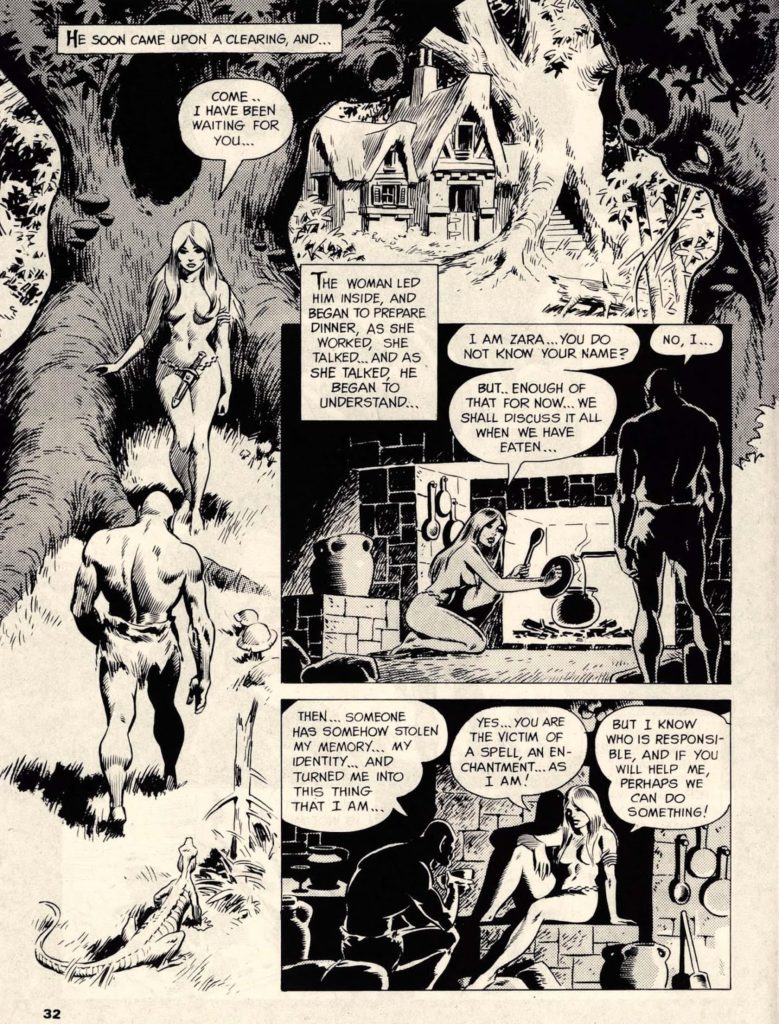

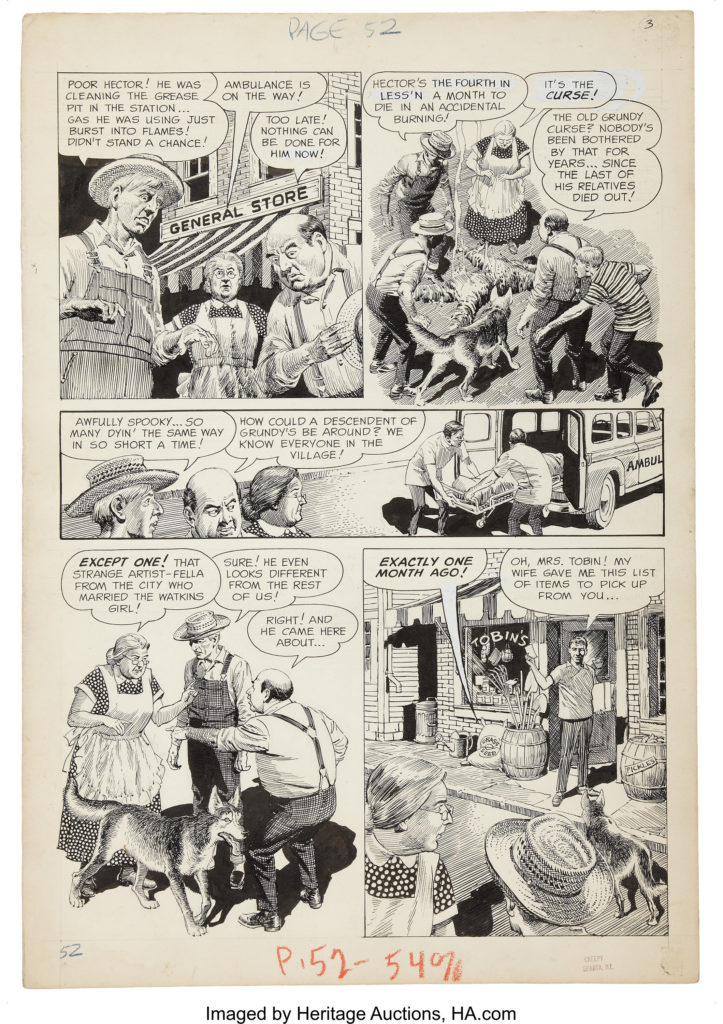

Crandall went on to become a mainstay of EC Comics, whose line of hit horror and science fiction titles would become as influential to future generations of comics creators as they were controversial in their own time due to their often graphic nature and mature themes. Joining a group that included artists Johnny Craig, Jack Davis, Will Elder, Frank Frazetta, Graham Ingels, Jack Kamen, Bernard Krigstein and Wally Wood, Crandall made his debut there with the six-page story “Bloody Sure”, written by Al Feldstein, in The Haunt of Fear #20 (August 1953).

He drew dozens of stories across a variety of genres for the EC anthologies Crime SuspenStories, Shock SuspenStories, Tales from the Crypt, Two-Fisted Tales, The Vault of Horror, Extra!, Impact, Piracy, and Weird Fantasy and its sequel series, Weird Science-Fantasy.

Marie Severin

Severin was working on Wall Streetwhen her brother John, then an artist for EC Comics, needed a colorist for his work there. Marie Severin’s earliest recorded comic-book work is coloring EC Comics’ A Moon, a Girl … Romance #9 (Oct. 1949). In a 2001 interview, she recalled she broke in as a colorist… for all the war books at EC with [Harvey] Kurtzman. I went on to color all their books, they were happy with it, and I learned a lot about production color and how everything worked. … I believe the color chart for the printed pages had a range of up to 48 colors. I had the full range; I would mix colors — golds, greens, blues, and so on — and you would intensify them so that the separators could see the difference. … What they liked is that I really studied which colors looked best and sharper next to one another, the subtleties of it. I would also proofread the colors.She would contribute coloring across the company’s line, including itswar comic and its celebrated but notoriously graphic horrorcomics, and also worked on the comics’ production end, as well as “doing little touch ups and stuff” on the art.

MotioMo

MotioMo