For every printing need there is a specific type of paper that will suit the job perfectly.

However, with so many different sheet types and sizes available on the market, it can be difficult to determine which ones can be used with your printer and which ones are right for a particular job.

Even when you’ve got to grips with the range of paper types and sizes, there are also different coatings and weights to choose from.

Printing paper types

Printing paper comes in many different types, each with different uses and benefits. Here are some of the most popular types of printing paper:

Inkjet Printer Paper

This type of paper is designed for specific use with inkjet printers. There are different forms of inkjet paper which work well with inkjet ink, including photo, glossy, business card, and greeting card variants.

Laser Printer Paper

Laser paper is best used with a laser printer. This is used more in business environments for tasks such as printing documents, cheques, and mailing labels.

Matte

This paper is one of the most frequently used, as it is suitable for all everyday printing tasks. Matte paper is finished with a white coating which helps the ink to dry faster than on other paper types, and means it is suitable for a document that is needed quickly.

Bright White

Bright white paper sheets are much smoother and are non-textured, which makes them ideal for high-quality, presentable double-sided printing. The brightness of the paper ensures that both sides can be printed on without the ink showing through on the other side.

Glossy

This paper type is traditionally used when printing images or photographs rather than text, as it has the ability to produce brilliant colours and sharp images. The glossy surface absorbs the ink, creating much higher clarity images than you could expect from matte paper.

Card Stock

This strong, sturdy paper type is most often used for scrapbooking or to print business cards and postcards. As it is significantly thicker than other types of printer paper, it is much more durable and can be carried and passed around without becoming tattered.

Resume

Slightly heavier than traditional paper, and with an off-white appearance, this type of paper is unique from other forms of printer paper. Resume paper features an ivory or cream tone and is commonly used for CVs or other important documents, to indicate that printed information is of high importance.

Paper sizes

A size

Most printer users are probably already aware of ‘A size’ paper. These are the most widely used, and easily distinguishable paper sizes. These paper sizes are simple to understand, as they increase and decrease in successive order, with A1 being the biggest paper size and A10 the smallest.

| Paper Size | Width x Height (mm) | Width x height (inches) |

| A1 | 594 x 841 mm | 23.4 x 33.1 in |

| A2 | 420 x 594 mm | 16.5 x 23.4 in |

| A3 | 297 x 420 mm | 11.7 x 16.5 in |

| A4 | 210 x 297 mm | 8.3 x 11.7 in |

| A5 | 148 x 210 mm | 5.8 x 8.3 in |

| A6 | 105 x 148 mm | 4.1 x 5.8 in |

| A7 | 74 x 105 mm | 2.9 x 4.1 in |

| A8 | 52 x 74 mm | 2.0 x 2.9 in |

| A9 | 37 x 52 mm | 1.5 x 2.0 in |

| A10 | 26 x 37 mm | 1.0 x 1.5 in |

A4

A4 paper is the most commonly-used for printing and measures 210mm x 297mm. This paper comes in many different weights and with several different coatings, meaning there is an A4 paper that is suitable for any printing job. This paper size is not only suitable for everyday tasks but can usually fit special purposes too.

A3

A3 paper sizes measures 297mm x 420mm, which is twice the size of A4 paper. This larger sheet allows you to print documents that need to make more of a visual impact, including large graphic pieces or high-resolution images. Large format A3 printers are extremely versatile as they have the ability to print in both A3 and A4, along with having faster print engines.

Other A sizes

Smaller A sizes such as A5 and A6 are also available, which are great paper options for printing flyers or other small media. There are also larger options like A2 and A1 which allow you to print posters and banners.

SRA

The SRA paper, or the ‘supplementary raw format A’ range is produced slightly more oversized than A size paper. Due to this it’s mainly used for commercial printing, as it allows room for bleeding, gripping and trimming. The most common size in this range is SRA3 paper, which can be used in many digital print machines.

C size

C size paper is a range of paper used exclusively for envelopes. The sizes vary from C1 to C10, and mainly correspond to their similar sizes in the A range of paper, although by design they are slightly bigger. This marginal difference in size allows the similar A size sheet to fit inside the envelope.

| Size | Width x Height (mm) | Width x Height (in) |

| C1 | 648 x 917 mm | 25.5 x 36.1 in |

| C2 | 458 x 648 mm | 18.0 x 25.5 in |

| C3 | 324 x 458 mm | 12.8 x 18.0 in |

| C4 | 229 x 324 mm | 9.0 x 12.8 in |

| C5 | 162 x 229 mm | 6.4 x 9.0 in |

| C6 | 114 x 162 mm | 4.5 x 6.4 in |

| C7 | 81 x 114 mm | 3.2 x 4.5 in |

| C8 | 57 x 81 mm | 2.2 x 3.2 in |

| C9 | 40 x 57 mm | 1.6 x 2.2 in |

| C10 | 28 x 40 mm | 1.1 x 1.6 in |

Paper weights

Image Credit: iStockPhoto.com / johnnyscriv (Via Custard Online Marketing)

As well as a range of paper sizes, there are various weights available for different uses.

Paper weight is generally measured in GSM. This stands for ‘Grams per Square Metre’ and is a measurement of paper thickness or density, which directly relates to the quality of the media.

The higher the GSM value of the paper, the thicker it is. As the description suggests, it indicates how much a 1 metre x 1 metre square piece of the paper would weigh in grams.

Generally, the thicker the paper, the more durable the sheet will be. Therefore, different paper weights have different uses, with thicker paper being used for more industrial purposes.

Common printer paper weights

| 300GSM+ | Good quality business card, or heavy card media |

| 180GSM – 250GSM | Middle market magazine cover |

| 130GSM – 170GSM | Promotional posters |

| 80GSM | Standard issue day-to-day office matte white paper |

| 35GSM – 55GSM | Most everyday newspapers |

Paper coating types

Printing paper can also be found with many different coatings, which will give the sheet a specific finish and thereby determine its suitability for a certain job.

Some of the most common paper coatings are as follows:

Varnish

These coatings can be found in either gloss, satin or dull finishes, and can be tinted in certain colours.

They are an incredibly affordable choice of coating, but have a lower level of protection compared to other laminates. Varnish coatings are useful for adding a gloss to a photo, giving a professional appearance.

UV

This coating offers a much higher level of protection to printed sheets and will enhance the printed colours.

It is applied as a liquid before being hardened under ultraviolet light, and can therefore vary in thickness. This coating can be applied either matte or gloss, along with specialised glitter or tinted finishes.

Aqueous

These coatings protect prints from fingerprints and other markings or damages.

Aqueous coating is fast to dry as it is water-based. Its major plus point is that these coatings are more environmentally-friendly than alternative options.

Paper opacity

Another thing to consider when purchasing printer paper is the opacity of the sheets. This refers to how transparent or opaque they are, or how much light they let through.

The weight of paper generally influences the opacity of the paper, with heavier paper usually being more opaque.

The opacity of a sheet of paper is measured on a scale of 0 to 100. A sheet which measures as 0 is a transparent sheet, while 100 would be a completely opaque sheet.

Different opacities will have different uses, for example, extremely transparent sheets can be used for tracing paper.

There you have it, a definitive, in-depth look at the different types of paper available on the market. This guide should clear up any questions or hesitations you have about which paper you need for your print job.

However, if you need any more assistance or have further questions regarding your printer, feel free to contact our team of experts who will be more than happy to help.

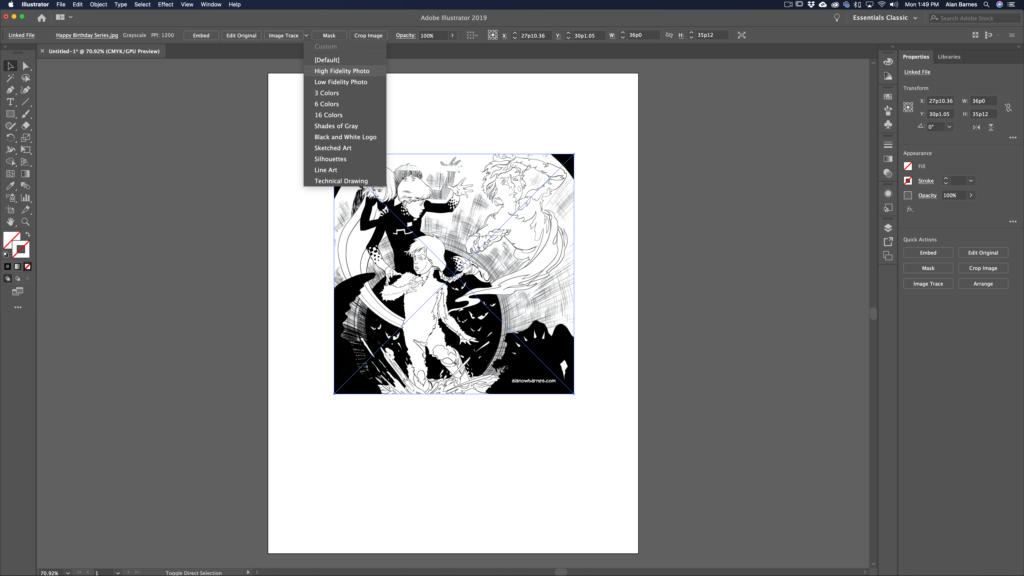

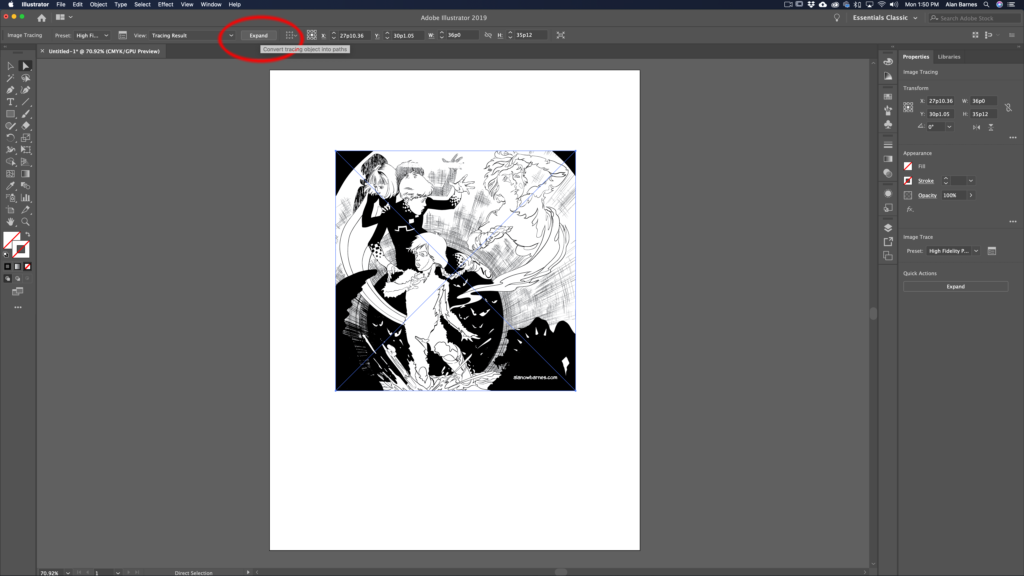

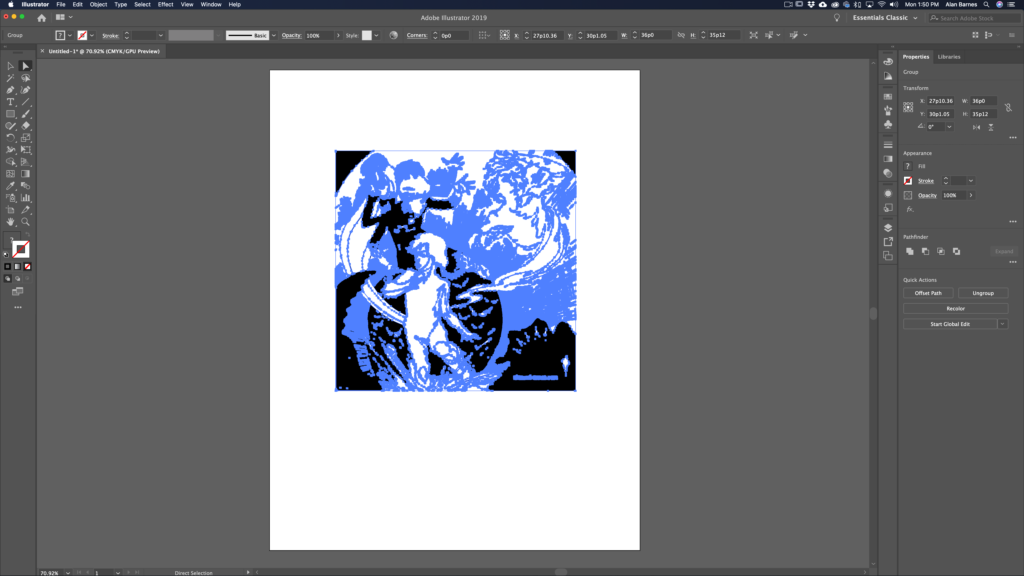

There are some “gotchas” related to this technique. For example: you will loose some of the fine detail intrinsic to drawing on paper. Brush details, and drawing effects will be lost.

There are some “gotchas” related to this technique. For example: you will loose some of the fine detail intrinsic to drawing on paper. Brush details, and drawing effects will be lost.